With COVID-19 still present, theaters remain empty and streaming services have gained more and more popularity. Even though people are no longer waiting in line for movies, a decision-making process still occurs. Movie lovers want to find something they’ll like or something that their family might enjoy. They search the internet, investigating sites like “Guardian” or “MTV” to see what’s “good.”

They turn to professional and amateur film critics to enlighten them on different aspects of the film they want to see. This has been the job of film critics for many years, starting in the 1920s. When there’s a lack of diversity among film critics, however, it’s hard for viewers to feel represented in film.

An 130-Year Tradition

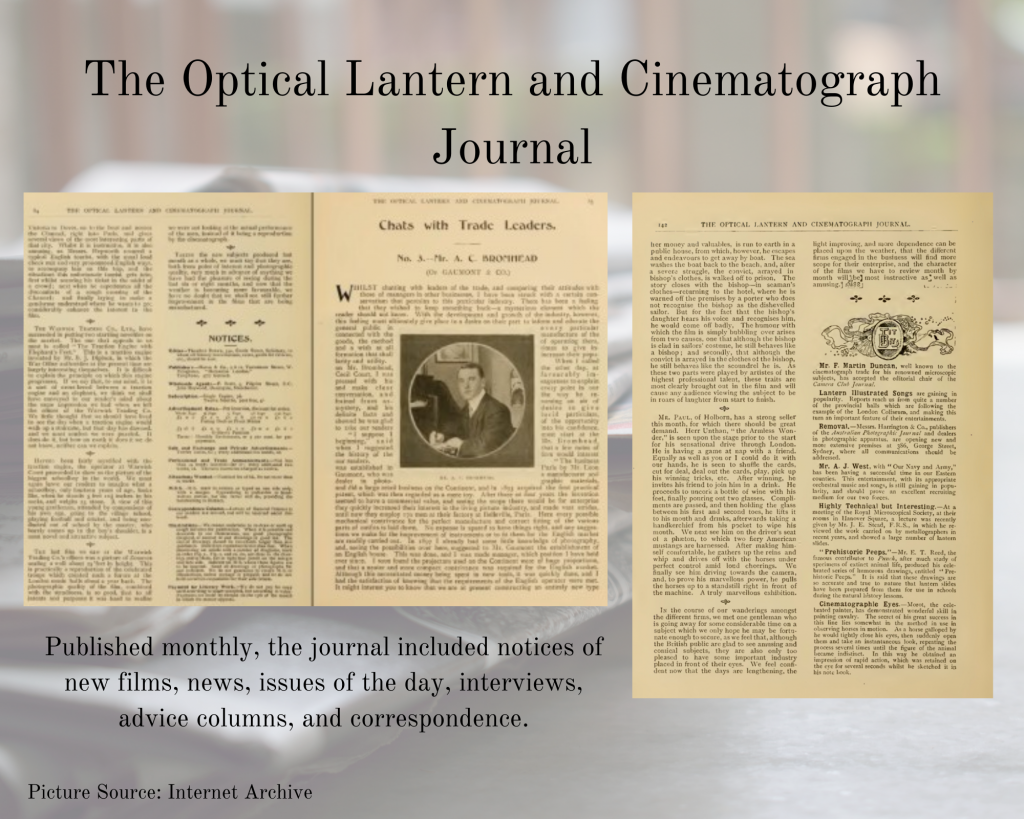

White men were the original film critics, starting in the late 1800s. The first paper to serve as a critique of film came from “The Optical Lantern and Cinematograph Journal,” which was created in 1889, going by “The Optical Magic Lantern Journal” before changing its name in 1904. The Journal focused on the up and coming film industry, sharing information about new films, information on new patents, interviews with filmmakers like producers Charles Urban and A.C. Bromhead, advice columns, correspondence and general news. However, this Journal was operated by majority white men because it was created for the film industry at the time, an industry run majority run by white men.

It wasn’t until the 1920s that critics were analyzing film for its merit and value as more than just entertainment. The growing popularity of the medium caused major newspapers to start hiring film critics. The concept of film critics only seemed to grow as red carpets and celebrities became more popular and the public wanted to know more about their favorite stars.

Film criticism changed from quick blurbs in newspapers to something more mainstream in the 1940s. Essays analyzing films with a distinctive voice and style worked to persuade the reader of the critic’s argument. This new style of writing gained the attention of many popular magazines and papers like The New York Times, Times, and Chicago Sun-Times and making film reviews a staple among most print media.

One woman who became a household name was Pauline Kael, a film critic in the 1960s. She wrote for The New Yorker until the 90s and was known for her witty, sharp style of writing. She reviewed films like “Lawrence of Arabia” and “Last Tango in Paris,” becoming one of the most influential American film critics of her era along the way.

Why It’s Newsworthy: Film diversity among filmmakers and film critics is an ongoing problem worldwide and in the Atlanta film scene. Organizations like Critics Groups for Equality in Media bring awareness to the problem and create a better environment for future creators.

A Lack of Diversity in Entertainment Industry

Now in the 21st century, film criticism is in high-demand with streaming services making any film accessible. This has made the lack of diversity in the entertainment industry more noticeable.

Valerie Boyd, Charlayne Hunter-Gault Distinguished Writer in Residence and associate professor of journalism at the University of Georgia, believes that the connection between filmmakers and film critics is important to the audience understanding diversity.

“There needs to be diversity in movie making. But of course, there also needs to be diversity in movie criticism, so that those same diverse people who are hopefully represented in the movies are also represented in the pool of critics so that we can say, ‘Oh yeah, they got this right.’”

A study done by GLAAD, which focused on the eight studios that grossed the most money from film releases in 2019, found that only 18.6% of contained characters identified as LGBTQ+. The only disabled LGBTQ character in a major film release that year was a gay Latino man with cystic fibrosis who appeared in “Five Feet Apart.” He died before the end of the film, and his death was used to push the two straight, white main characters close together.

While that data is now four years old, things have not shown significant improvement in recent years. An article released in 2020 discusses data gathered by the Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film, which found that male critics outnumbered female critics by a ratio of nearly 2-to-1 and that 70% of the female critics were white.

Controversy Within Film Criticism

While being honored at Women in Film’s Crystal + Lucy Awards, Brie Larson, actress and filmmaker, spoke passionately about the lack of diversity in film criticism. She explained that Ava DuVernay’s “A Wrinkle in Time” was one of the many films that desperately warranted a more diverse critics’ pool.

The film is based off of the 1962 novel that tells the story of a young girl who, with the help of three astral travelers, sets off on a quest to find her missing father. Ava DuVernay, the director of the film, imagined the lead of the film to be a black girl and give the lead role to Storm Reid. Oprah Winfrey, Reese Witherspoon and Mindy Kaling were casted as the three astral travelers.

Many of the white, male critics found that the film “has no flow whatsoever” and “has tons of issues.”

“The Help,” a film released in 2011, tells the story of two black maids and a young, white writer during the Civil Rights Movement in 1963 Jackson, Mississippi. The film mostly received positive reviews when it was released, but some critics, like Boyd, found the film to have a “white savior” narrative. She wrote in her 2011 review of the movie that the film “is a feel-good movie for a cowardly nation.”

Those strong words set the tone for her review, with Boyd explaining how the film doesn’t center around “the help,” but around the white women intertwined in their lives. And the ending of the film is “falsely uplifting” with the white writer getting her dream and the black maid losing her job. But the issue with all of that, Boyd points out, is that “filmmakers expect viewers to feel good about this. The problem is, many white viewers will.”

Viola Davis, who played Aibileen Clark in “The Help,” cites her role in the film as one of her biggest regrets. When asked why she regrets the project, she explained that the story just wasn’t about the maids, but about the white characters that “saved” them. While this film was one of Davis’s biggest “hits” to date, she regrets pushing forward the white savior narrative, instead of centering the film around the maids.

While many didn’t agree with Boyd in 2011, some followed her lead, quoting her in their articles and creating more of a conversation. New reviews on the film coming out in 2020, agreeing with Boyd’s original opinion of the “white savior” narratives like this review done by the Insider or USA Today. The film has taken on new meaning as time has passed, and Boyd’s opinion has become the majority over the past 10 years.

Social Media Movements

“What is required is a concerted and intentional effort to close the gap. So there’s a movement. It’s related to the viral hashtag #metoo movement called Time’s Up. And it’s a movement in Hollywood to close the pay equity gap between men and women, and to close the sort of representation gap of women as well,” Boyd said.

The #metoo movement became a viral hashtag on social media starting discussions of sexual harassment, particularly in Hollywood and led to high-profile firings. The Time’s Up movement was created in response to the sexual harassment cases in Hollywood, related to Harvey Weinstein that started coming to light in the fall of 2017.

Other social media movements included the #AskMoreOfHim with the goal of having men speak up about not only sexual assault, but how to make women more equal in the industry. And #OscarsSoWhite movement pushed for more inclusivity and diversity among nominees at the Academy Awards after the 88th Oscar nominations faced major backlash when there was only one nominee out of the main Oscar categories that was ethnically diverse.

Steps Toward Diversity

Six national critics organizations have come together and created the Critics Groups for Equality in Media (CGEM). The coalition’s goal is to improve awareness of the value of diverse groups such as women, people of color, LGBTQ and the disabled who cover the world of film. The coalition’s goals include pushing for equal pay and inclusive representation, strengthening relationships with studios, networks and public-relations firms and to “nurture next-generation voices in entertainment journalism.”

The six underrepresented groups — the African American Film Critics Association (AAFCA), the Features Forum of the Asian American Journalists Association (AAJA), The Society of LGBTQ Entertainment Critics (GALECA), the Latino Entertainment Journalists Association (LEJA), the Online Association of Female Film Critics (OAFFC) and TIME’S UP Entertainment — have formed CGEM to give the unique voices they represent their time to shine.

In 2019, their official press release allows directors and presidents of the organizations above to explain their passion for the issues and why it really is so important.

While there hasn’t been any announcements on official programs, the coalition is interested in exploring initiatives, like a “watchdog component” that will grade studios, networks and publicity firms on their engagement with the individual critic associations. They are also looking into an awards program to honor publicity and media executives who support equality in the entertainment industry.

Overall, these critics are trying to do what they can to make sure that every voice is heard and respected. They are also starting the conversation, forcing professionals in the industry to take a look at the problem in front of them.

“I feel like critics have the power to shape the conversation,” Boyd said.

Megan Grantier is a senior majoring in journalism at the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication with a minor in film studies.

Show Comments (2)