Cotton—a plant many Americans associate with the Deep South—arrived in Georgia, the first colony to produce cotton commercially, in 1734. After the development of Eli Whitney’s cotton gin in 1794, the production has only increased.

Ronnie Hardigree, 71, has been growing cotton since 1973 but purchased his first tractor when he was 16 years old. His family farm, Wild Cat Creek Cotton Plantation, was established in Watkinsville, Georgia, in 1905 and has been operating for the past 115 years.

Why It’s Newsworthy: Gossypol is a toxic substance found in cottonseed that limits its uses. A research team at Texas A&M University has created a new genetic trait that grows Ultra-Low Gossypol Cottonseed (ULGCS), which could help address many global challenges and create more income for Georgia’s farmers.

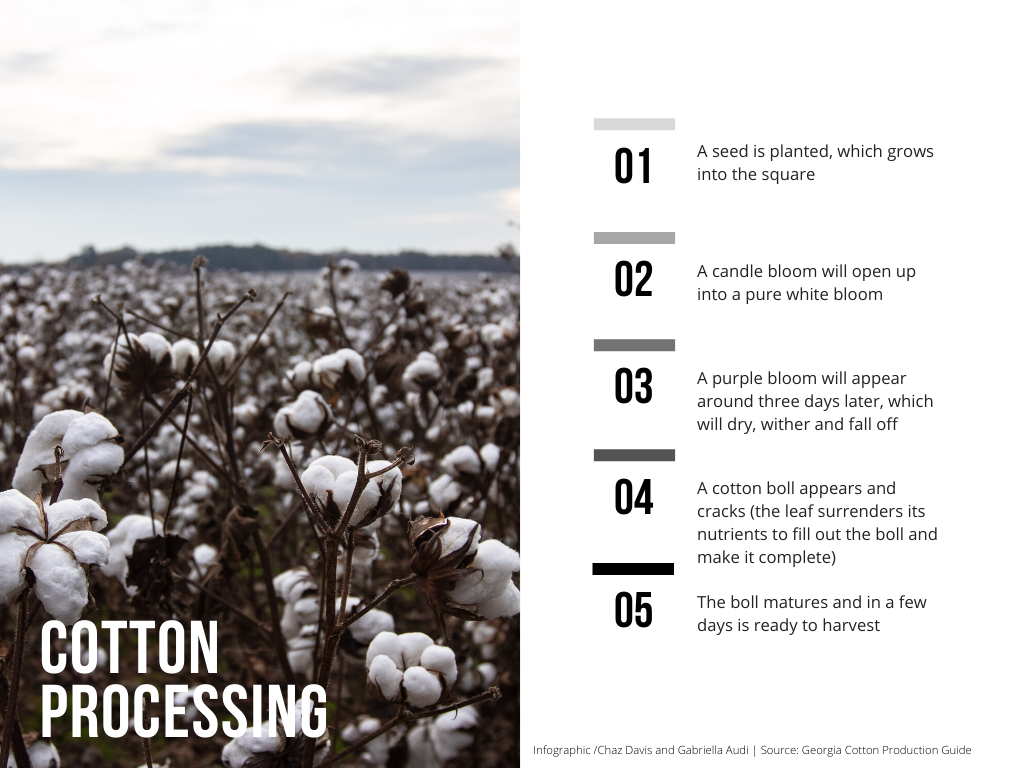

Cotton as a Crop

When people think of cotton, images of soft, white balls of fluff grown in rows and rows of open fields next to long, winding country roads may come to mind. This ball of fluff is called lint, and it covers another aspect of the plant not usually thought of: the cottonseed.

Jared Whitaker, an assistant professor in crop and soil sciences and a cotton agronomist at the University of Georgia, said that both the lint and the seed are important to cotton farmers.

“Cotton is the number one row crop [in Georgia] in terms of acreage and the most widely planted,” said Whitaker. “A farmer grows the cotton plant and it produces bowls which are the cotton fruit, that have seeds that have hair on the feet which is called lint. Farmers get paid for the seed and the lint.”

The soft, white lint is used to make textiles like shirts and jeans, which is where most of the profit is derived from, Whitaker said. But other parts of the plant are used to make common household items.

For example, the small fuzz covering the exterior of the cottonseed can be converted into cellulose, which is used to manufacture glass screens for smartphones and televisions.

After harvesting his cotton, Hardigree sells both the lint and the cottonseeds to be processed and manufactured into various items.

“They put [the cottonseed] in a warehouse and then they store them and they sell them to dairy farmers, oil seed factories, you know, people who can take them and process them further,” Hardigree said.

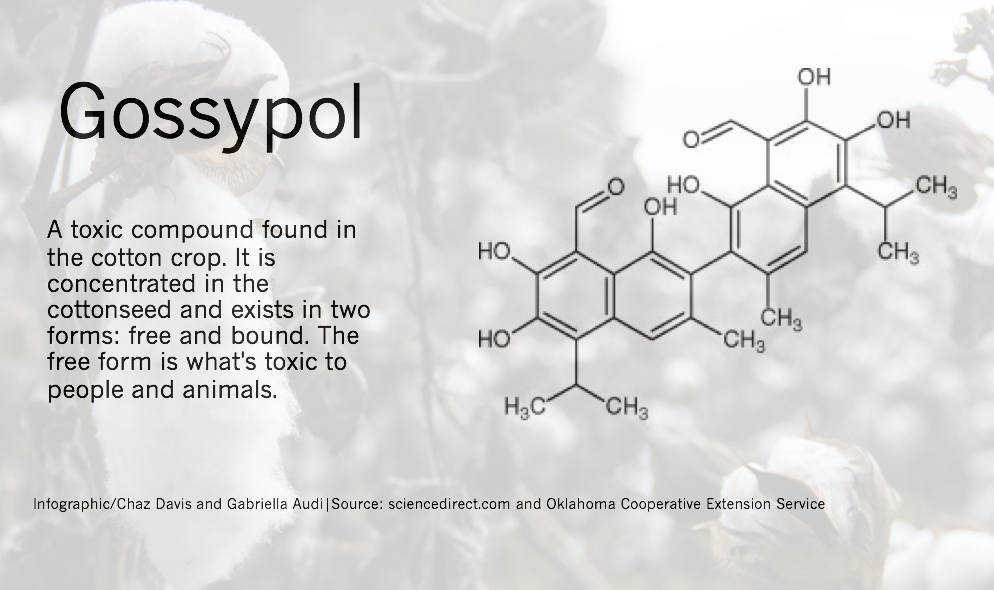

Gossypol: The Barrier to Better Cotton

One important evolutionary trait of cottonseed is gossypol, a naturally occurring compound in the cotton crop. It acts as a built-in pesticide, helping the plant produce as much lint as possible.

However, gossypol makes cottonseed toxic for people and most animals. In humans, it can cause weakness, depression, damage to the digestive system and reproductive problems. In animals, it affects the heart and liver, but it can be used in low amounts as feed for cattle and sheep.

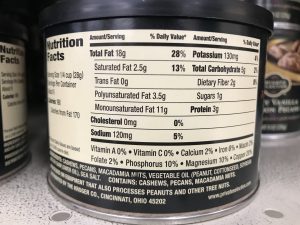

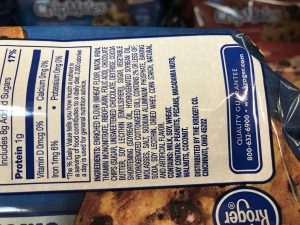

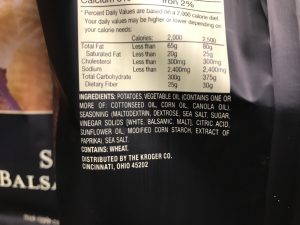

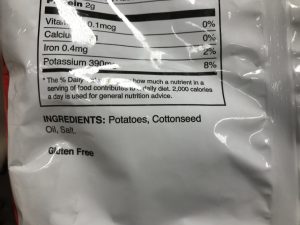

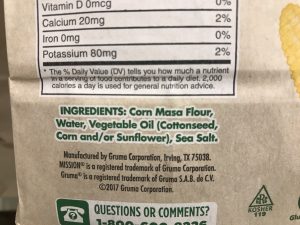

Despite the seed’s toxicity, cottonseed oil can be consumed by humans because the gossypol is removed through an oil refining process.

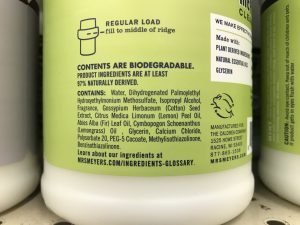

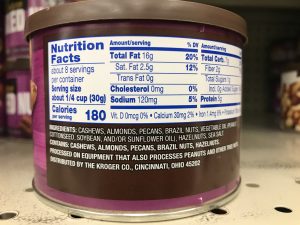

Cottonseed oil is used in several food products including peanut butter, chips, cookies, crackers, salted nuts, mayonnaise, margarine and salad dressing as well as in some cosmetics and lotions. It is also popular as a frying oil because it’s cheap and doesn’t mask flavor like soybean and canola oils do.

Despite its varied uses, cottonseed oil is not especially valuable. For that reason, cottonseed is treated more as a byproduct, Whitaker said.

A Gossypol Breakthrough

Keerti Rathore is a professor at Texas A&M’s Institute for Plant Genomics and Biotechnology. He has dedicated decades to the science of genetically modifying common crops like rice, corn, cotton and potatoes to improve them.

Rathore said Ultra-Low Gossypol Cottonseed (ULGCS) could be one of the most impactful developments he has been involved with.

“We have removed [the gossypol] selectively in the cottonseed without affecting the levels of this toxic terpenoid in other parts of the cotton plant, where it’s needed to defend the plant against insects and some diseases,” Rathore said.

As its name suggests, the ULGCS project is dedicated to creating a cotton plant that develops seeds with low levels of gossypol. After 25 years, the project has nearly reached fruition; the ULGCS genetic trait was successfully created and has moved through the deregulation process.

Without adequate funding, it was difficult for the team to develop the tools and technologies needed to complete their research, Rathore said. Failed attempts along the way strained resources and lengthened the project’s duration.

The implications of a non-toxic cottonseed could permeate multiple industries. Rathore said extensive testing has shown that Ultra-Low Gossypol Cottonseed is safe for both humans and animals and creates a new source of protein that could see widespread use and consumption.

“Now we can take the cottonseed and even use it directly for human nutrition. Or we can use this cottonseed to feed the chickens or the fish or the pigs,” Rathore said. “And the reason why it’s more important to feed it to animals other than cows is that these animals are anywhere between three to seven times more efficient compared to the cows in terms of converting feed protein into edible animal protein.”

Future Opportunities with ULGCS

Cotton grows well in many regions of the world struggling with hunger amidst high rates of population growth; Rathore said Ultra-Low Gossypol Cottonseed grown across the world could meet the protein requirements of roughly half a billion people.

Using cottonseed as a source of protein could also mean several other things. For one, cottonseed would become much more valuable and in-demand, meaning that more money would end up in the pockets of cotton farmers and help fuel Georgia’s economy.

“It certainly would change things if we were able to use the seeds from cotton,” Whitaker said. “If it was as valuable as the lint, it would be a lot better for the farmers if they actually got value for the seed.”

Since cotton is already being grown, more land will not necessarily need to be cleared for Ultra-Low Gossypol Cottonseed production — it will just double the value of the cottonseed already being produced. And if this new protein source is embraced by the food and cattle industries, it could reduce the destruction of the Amazon rainforest, which is being cleared partly to grow a major source of plant-based protein: soybeans.

“The demand for protein is so high, and soybean happens to be the biggest source of protein for a lot of things,” Rathore said. “So if we can bring this other source of protein into the market, that pressure on the forest goes down some or substantially, I hope.”

The ULGCS trait has already been approved by the Food and Drug Administration and the United States Department of Agriculture, meaning the ULGCS cotton can be grown in the U.S. without a permit.

It might take a long time to integrate ULGCS with current cotton breeds since the genetic traits of cotton vary around the world, but Rathore feels confident that change will happen.

Gabriella Audi, Chaz Davis, Alex Vanden Heuvel and Emma Toland are seniors majoring in journalism at the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at The University of Georgia.

Show Comments (0)