“It was like a heroin addict quitting cold turkey,” said William Breedlove.

In 2011, Breedlove incorporated the 345 acres his family owned for four generations into The Pastures of Rose Creek. Originally a dairy farm turned fields for rent, Pastures of Rose Creek was converted into a 100 percent pesticide-free, fertilizer- and hormone-free farm for the benefit of the animals and farmland.

“The farm had to detox. It went into, like, a really nasty phase, looking rough for like a couple of years,” he said.

According to a 2017 German study, the average organic diet uses about 40% more land than the average conventional diet to maintain an equal amount of food produced.

While Breedlove currently has a total of 83 cows and 700 to 900 chickens on his 188 acres of pasture land, his focus is on quality rather than quantity.

“I’m not interested in feeding the world, I’m interested in feeding my area. And I think that, if more places in the world was more interested in feeding their areas, then it would be better for those individual areas,” he said.

Breedlove’s main focus is feeding the community around him.

He stated, “shipping is like one of the biggest pollutants. Why buy something from California when you can grow it here or, you know, change your diet to eat local versus, like, spending millions of dollars to ship things.”

Breedlove practices rotational grazing with his cows and chickens, which helps him save electricity, water and carbon emissions.

After he stopped using chemicals and started rotating his animals, Breedlove’s land began acting as a carbon sink, meaning that it absorbs more carbon than it releases.

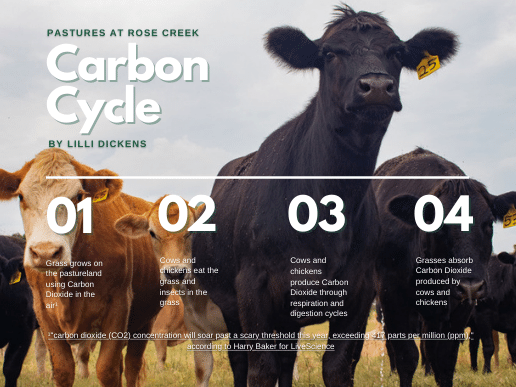

Breedlove does not use tractors or other equipment that produces large amounts of carbon. The only significant producers of carbon at Pastures of Rose Creek are the cows and chickens, who eat the grass and bugs in the grass.

The grass, in turn, uses the carbon dioxide already in the air and that produced by the animals on the farm, so there is more carbon being absorbed than produced.

Breedlove’s use of solar panels started with his movable chicken coop, which he has nicknamed “The Egg Mobile.”

“I needed to find a way to keep my dogs that [guard] my chickens near the Egg Mobile. And I can’t just run power lines anywhere that the Egg Mobile is, so I use solar panels to charge the shock collar system that keeps them near… Without it, they’ll run away. And Pyrenees dogs travel. So like, if you can’t contain them, they’ll just go off,” he said.

He also uses solar panels to power the electric fences around his cattle.

In 2007, the United States Environmental Protection Agency reported there was as much as 3,810 kilograms of nitrogen and 1,165 kilograms of phosphorus in the ground per square kilometer of farmland in the state of Georgia due to runoff from animal waste. Breedlove found a solution to avoid this.

There are three creeks that run through Pastures of Rose Creek, but Breedlove does not use them to water his cows and chickens.

“I have wells…instead of using creeks and lakes, [because] cows would create an unhealthy water supply,” he said.

“We pipe water directly from my wells to troughs so it’s pure. It’s the water that we drink, it’s the water that they drink, so you don’t have to worry about bacteria in the water that you get from other creeks and neighboring farmers… all those things go into the water and pollute the waters, our cows [and chickens] don’t get that,” Breedlove said.

“And it’s better for rotational grazing, because if you can build [a trough] in the middle of your field, then you can use the middle of the field as the center part that you can rotate around. … Picture my field like a pizza, and if you take a slice, that would be the slice where my cows are. And then if you take another slice out, that would be the slice that they go to next,” he said.

One hundred percent chemical-free farming has also helped Breedlove save money, as well as the health of his land.

“If you’re fertilizing 100 acres with sprayed fertilizers, it’s gonna cost you like $100,000. I use chickens [manure] that I collect eggs from and make money,” he said.

However, Breedlove was not able to accomplish this all on his own. The Natural Resources Conservation Service helped make Pastures of Rose Creek into what it is today.

The Georgia division of the Natural Resources Conservation Service exists to “work with people through a partnership effort to conserve and protect natural resources,” according to their website.

Jose Pagan, the district conservationist for the NCRS, helped Breedlove find a few programs for his farm.

“[Pastures of Rose Creek] used our ACEP [Agricultural Conservation Easement Program] programs to help sell their development rights…and our EQIP [Environmental Quality Incentives Program] program to assist in building their fences and troughs,” Pagan said.

After 10 years of chemical-free farming, Breedlove’s animals and land are healthier than ever.

“Our grasses got too good last year, and my calving season was a little late…my mother [cows] were producing the calves, but they were growing too big before they were born…calves should be born in between 60 and 80 pounds, and my calves were like 150 pounds,” he said.

Lilli Dickens is a senior majoring in journalism and minoring in Spanish at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (2)

SolarSME

Renewable energy is the best alternative to reduce carbon footprints and emission of gases.