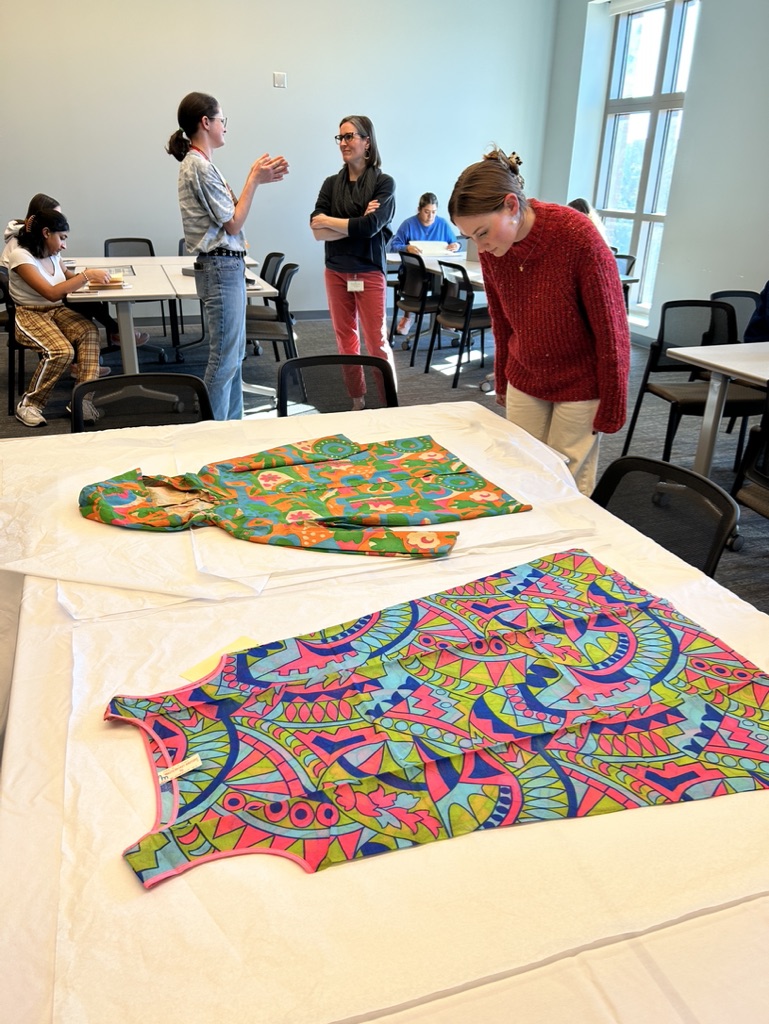

A pair of fluorescent, color-blocked dresses drape across the desk, bursting with shades of pinks, blues and greens still as vibrant as they were so many decades before. Atop the neighboring table are folders of black-and-white photographs, some discolored with age and others curled at their edges. A book with a well-used spine rests on yet another table.

Conversation floats across the room in the Special Collections Library, while classmates gather around the items and inspect them with intrigue.

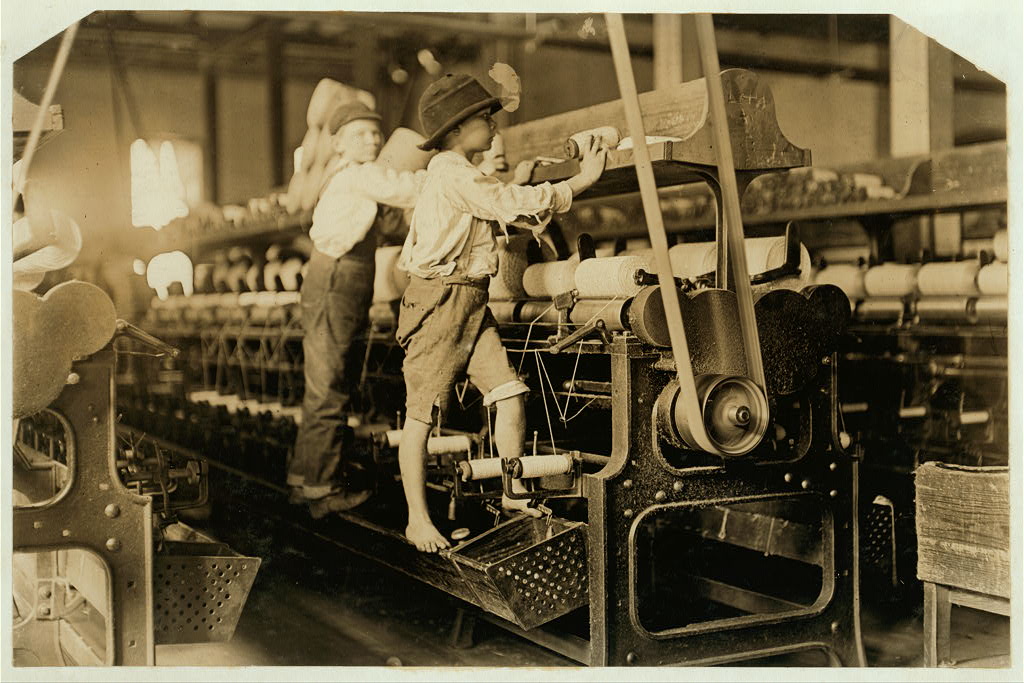

The garments, which are made of paper, are evidence of the disposable clothing trend that took the mid-1960s by storm. The images depict cotton mill workers across Georgia in the 1910s, and the book is an 1892 copy of “How the Other Half Lives” by Jacob Riis, documenting working-class living conditions in New York City.

Each historic object reflects a change in textile and clothing production and plays a key role in Sara Idacavage’s investigation into how material culture can be used to educate and enrich her fashion and sustainability class.

The fashion historian-archivist-educator spent the past semester centering her College of Family and Consumer Sciences special topics course around historical clothing practices and how they can be analyzed and aligned with fashion in a modern context. Through open discussions and experiential learning, such as the field trip to the library on Monday, Feb. 6, Idacavage hopes her students can apply their classroom lessons to the world and their daily lives.

Why It’s Newsworthy: Sara Idacavage used experiential learning and interdisciplinary skills to teach her students about sustainability and fashion. Ultimately, Idacavage wants her students to be able to take what they have learned in the classroom and apply it to their lives.

“We’re talking about sustainability in these really abstract ways, and I think holding, for example, photographs of children working in textile mills in the early 1900s, [brings us] face-to-face with the past,” said Idacavage. “I’m holding this object that connects me to those people physically.”

After graduating from the University of Georgia in 2009 with her bachelor’s degree in fashion merchandising, Idacavage moved to New York City to pursue a Master of Arts in fashion studies at Parsons School of Design.

There, she began to frequent stores such as Zara and H&M, which were within walking distance from her office. These retailers offered her greater access to — and selection of — styles she seldom found during her undergraduate years. However, her energy to shop on a routine basis weakened over time, and her enthusiasm for exploring personal taste was replaced with growing uncertainty and concern for where exactly such garments came from, and where they were headed.

According to the Bloomberg article “The Global Glut of Clothing Is an Environmental Crisis,” in 2021 alone, Zara offered 50,000 new and unique styles on its website, while H&M had 25,000. Idacavage soon found herself returning to Goodwill at the end of each season, with bags full of discarded clothes that she found carried as much mental weight for her as physical.

NOTE: Click “Scores” to see the data change.

Concurrently, Idacavage had been working within museum and archive spaces, as an assistant fashion archivist, then as an archives specialist at the New School and as a costumes and textiles collection intern at the Museum of the City of New York. These valuable experiences helped her become conscious of how certain textiles and material felt in comparison to others, in terms of durability and quality, and she began incorporating second-hand garments into her everyday wear.

“As much as I am adamantly anti-fast fashion for many reasons…I have to give that some credit for helping to form my style identity,” Idacavage said.

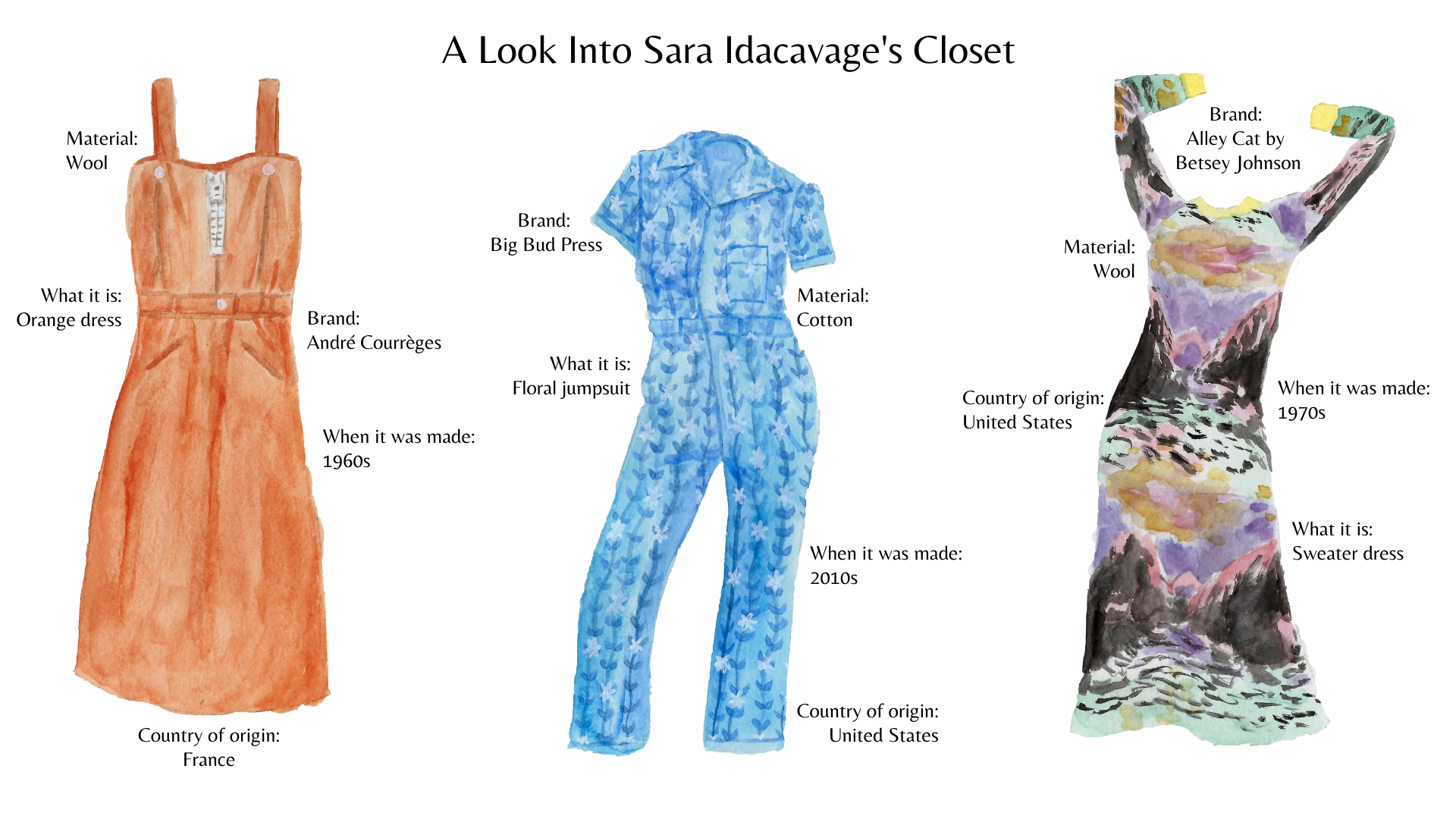

Now, Idacavage’s wardrobe is home to an array of vintage apparel and accessories, ranging from an apricot-hued André Courrèges dress; to a rare, 1970s Betsey Johnson knit dress and to flats inspired by Piet Mondrian. She uses these often-unique items as material to teach and to storytell.

She prioritizes informing her students on what she gained from her closet’s evolution, as well as what she wished she knew at their age. An afternoon spent at a municipal solid waste landfill teaches students how household refuse is broken down, and outings to second-hand boutiques and refilleries inform them on the importance of clothing care, while also introducing them to fellow Athenians who have adopted eco-friendly practices.

One such example is Totally Taylored, a sustainable shop that the class visited on Friday, March 31. Owned and founded by Taylor Ooley, the store offers refillery services, home goods made of discarded fabrics and products from other small businesses. Ooley, who is a seamstress, unexpectedly began her entrepreneurial work four years ago, when she came across old textiles at her mother’s house and upcycled them into tote bags, instead of throwing them away. Her storefront welcomes customers from varying walks of life, regardless of where they are on their journeys to adopting more sustainable lifestyles.

“[I] just want everyone to know that there’s a space for them here. I’m really trying to combat [the] damage that has been done by the zero-waste mindset that has really excluded so many people from feeling like they can have an environmental impact,” Ooley said.

This all-or-nothing state of mind often pushes individuals to experience eco-anxiety, eco-guilt and related stressors. Eco-anxiety is defined as ‘a chronic fear of environmental doom’ in “Situating Sustainability: A Handbook of Contexts and Concepts” and can lead to feelings of powerlessness and, ultimately, defeat, especially when paired with one’s personal perception of their contributions to the ecological crisis.

Fortunately, by curbing judgment, Ooley is able to connect with and help patrons, new and old, seeking ways to lessen their consumption. Similarly, Idacavage’s own acknowledgment of her past with fast fashion and willingness to use it as a learning experience, rather than something to hinder her growth, shows her students it is never too late to transform consumption habits, so long as they are putting in the effort to do so.

“You can’t do sustainability in a vacuum,” said Haley Allen, a seamstress at Community, the slow-fashion boutique that Idacavage’s students explored on Friday, Feb. 17. “You get so much more joy out of collaborating with people, and you come up with ideas and meaningful projects that you wouldn’t have on your own.”

As the fashion sustainability students learned, when working on clothing alterations and custom pieces, Allen brainstorms with her clients and coworkers to ensure the goods are of satisfaction for each party involved. The value of collectivism is practiced within Idacavage’s classroom, and Ashlyn Daughenbaugh, a student in her course who is studying fashion merchandising, social entrepreneurship and sustainability at the University of Georgia, said the class is a space where students can be authentic and, when needed, can confront their classmates to foster awareness.

“This is a group of people that I can be honest with. They can be honest with me. We are making a lot of discoveries together, and it really feels like all of our work is cumulative and we are all building on top of each other’s skills,” Daughenbaugh said.

This uplifting, communal effort saw itself through during the class’ demonstration at Tate Student Center for Fashion Revolution Day on Monday, April 24. Begun in 2013 as a response to the Rana Plaza factory collapse, which killed over 1,000 factory workers and is considered to be among the worst ever industrial accidents, the activism movement Fashion Revolution aims to raise awareness of the global fashion industry’s faults.

Throughout the activity, Idacavage and her students asked passersby if they knew or ever thought about where their clothes were made, offering them informational handouts and buttons, which read “who made my clothes?” The students stood on the tips of their toes to peer over shirt labels and kept track of the garments’ countries of origin on a map, which, by the end of the event, had markings across Brazil, China, Indonesia, Mexico and the United States.

“Starting the conversation is a good place to begin your activism without making people feel guilty or shying [them] away from sustainability,” Daughenbaugh said.

As Idacavage and her students held up their demonstration signs and chanted “de-fashion,” their voices grew in unison. Forming connections with one another, with history and with their communities reveals the value that experience brings to first acknowledging, then understanding and actively responding to the many facets of eco-consciousness.

“This [class] is the first time I’ve, in some ways, been given this…responsibility of how to present this information in any manner that I like,” Idacavage said. “So it’s really what I’ve been building up towards, I think, my entire career, my entire life.”

Skyli Alvarez is a senior majoring in journalism and minoring in art history.

Show Comments (0)