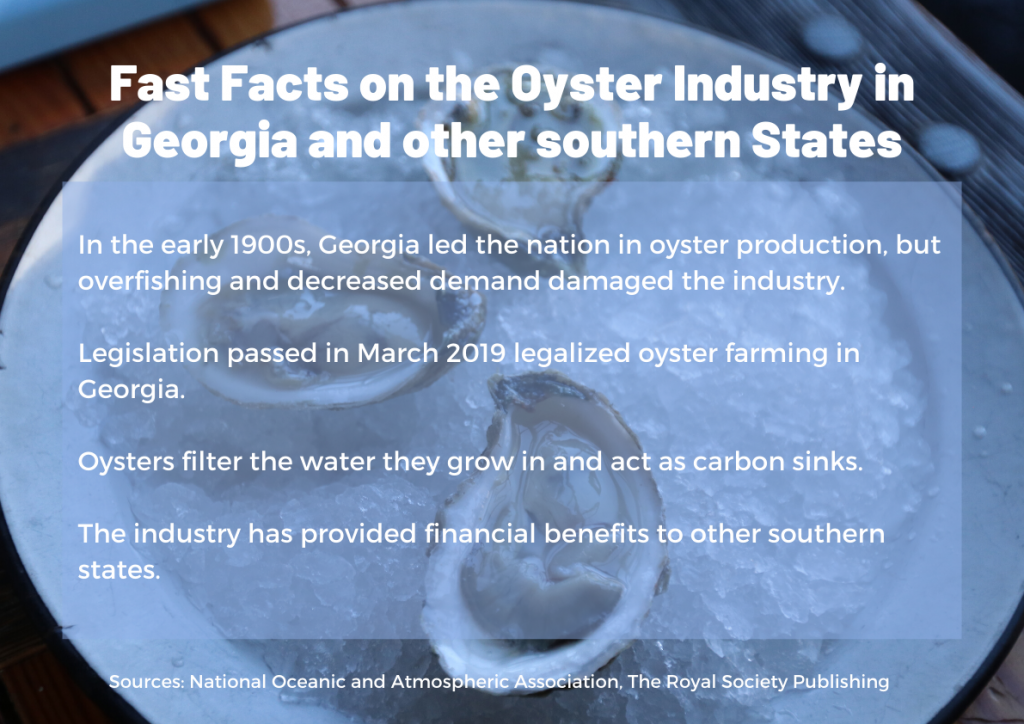

Georgia is known as the Peach State and is famed for its peanut-farming president, but more than 100 years ago, Georgia was leading the nation in a crop with origins in the ocean rather than on land. In the early 1900s, the state was number one in the country for the oyster industry, harvesting oyster meat to feed the thriving canning industry.

Nowadays, Georgia’s coastline is a little quieter. It’s been many years since Georgia has dominated the oyster business, as oystering in Georgia suffered from over-harvesting and decreased demand. In the meantime, other southern states such as Alabama, Florida and the Carolinas have cashed in on oysters, becoming strong contenders in a business that has been traditionally centered around the Chesapeake Bay area.

However, oyster enthusiasts are hopeful that the industry will make a comeback in the state. Legislation passed in March seemed intended to pave the way for the resurgence of the oyster industry in Georgia by legalizing oyster farming. Previously, oystermen could only harvest wild oysters, which vary in size and shape, while farmed oysters tend to be more uniform and consistent in shape.

Why It’s Newsworthy: Legislation passed in March 2019 legalized oyster farming in Georgia, but those familiar with the oyster industry criticized the legislation for being too regulator-focused. Oyster farming could have many environmental and social benefits for the state.

While on the surface, this legislation appears to be a step in the right direction to revive this once-thriving mollusk, some see the new law as hindering the industry before it ever gets a chance. And although Athens is about four hours from the coast, the potential revival of Georgia-grown oysters has an impact on local seafood restaurants.

Evaluating the Pros and Cons

Noah Brendel, co-owner of Seabear Oyster Bar, said he has always found the lack of Georgia-grown oysters to be frustrating when deciding what to put on the menu at his restaurant.

“We have one of the prettiest coastlines and one of the healthiest estuaries out of all the southern states, if not the eastern seaboard,” Brendel said. “Georgia is behind in the oyster fishery program.”

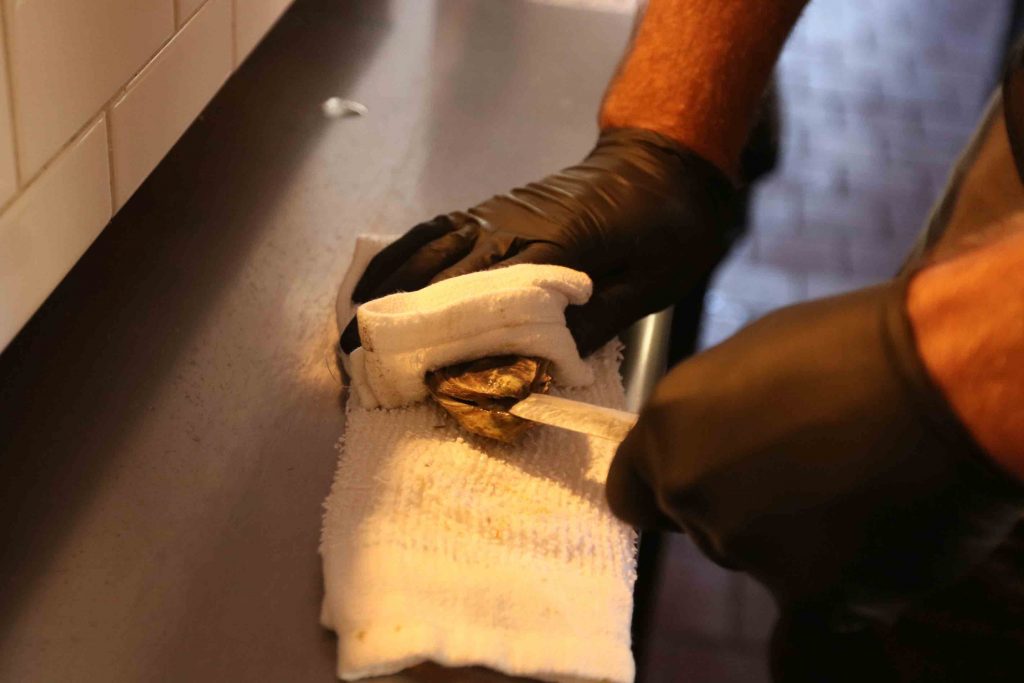

On Oct. 14, Seabear offered oysters from Maine, Maryland, New York and Nova Scotia. The restaurant also recently received a shipment of 400 oysters from Earnest McIntosh, one of the small oysterman business owners trying to make a living cultivating oysters in McIntosh County, Georgia.

Ironically, although Seabear is only about a four-hour drive from the Georgia coast, Brendel said Georgia oysters are the most expensive oysters that the restaurant purchases.

“We get oysters from Canada for cheaper, because they’re coming from a distributor who has all the distribution channels set up,” Brendel said. “Earnest is an old man who has always done things in an old, meticulous, southern kind of way, and is just now getting into this, turning it into a business that reaches outside the coastline.”

Brendel said this is Seabear’s second year selling Georgia-grown oysters, and they “fly out the door.”

“People love them, and we love them,” Brendel said. “If we had more Georgia oyster options, we would probably keep three or four on [the menu] when they’re in season.”

Oysters: Slimy, Salty, Sustainable?

Ask Brendel what he likes about oysters, and he says simply, “everything.” He likes the fact that oysters are full of vitamins like zinc and B12. He also likes the variety you get with oysters from different locations.

“It’s kind of like wine,” Brendel said. “An oyster from Maine is going to have a lot of deep seaweed, really salty, briny, cold-water feel to it, whereas an oyster from Florida is going to take on more mineral elements from the water.”

But from an environmental point of view, Brendel said he likes the service that oysters provide to the ocean. Oysters filter the water they are cultivated in and oyster reefs sequester carbon and help strengthen shorelines.

We are farming something that’s giving back to the environment in which we’re farming it in, as opposed to taking, which is what farming typically does,” Brendel said.

In addition to providing a sustainable benefit to the ocean environment, oysters might also be able to contribute to creating more resilient communities by providing new jobs.

McIntosh County, where Earnest McIntosh conducts his oyster business, has a poverty rate of 20.3%, which is higher than the 2018 national average of 11.8%.

McIntosh County has the highest poverty rate of Georgia’s coastal counties, while Alabama’s two coastal counties have more divergent poverty rates.

Brendel said he hopes the state government will prioritize funding for the development of oyster farming to bring prosperity to Georgia’s coastal counties.

“I wish our state could get its priorities together and realize that what they will get is providing jobs for people in otherwise really poor places,” Brendel said.

Taking Cues From Our Neighbors

Andre Gallant, author of “A High Low Tide: The Revival of a Southern Oyster,” and a part-time instructor at the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia, said a main complaint with the legislation, House Bill 501, is that it seemed to benefit the industry regulators rather than the business owners themselves.

“It’s a bill that made it easier for regulators to regulate, that was the focus of the bill, instead of how can we help these small business people grow their businesses?” Gallant said.

Another frustration people in the oyster industry had with the bill is that people are seeing the positive growth that neighboring states like Alabama, Florida and North Carolina are experiencing with this industry, and wondering why the same practices can’t take root in Georgia, Gallant said.

“The frustration here in Georgia was that why aren’t we following their lead?” Gallant said. “We don’t have to reinvent the wheel. We have industry partners across the region that we can call on for help.

The success that our southern coastal counterparts have seen in a short time from the growth of their oyster farming industries is undeniable.

In 2009, Alabama didn’t have a single oyster farm, but now, the state boasts 13 such farms. These farms are providing jobs for locals, and their oyster products are catching the eye of high-end seafood restaurants.

Shellfish cultivation in Florida is mainly focused on clams, but Florida was fourth in the nation in 2013 in mollusk sales which brought in $19.64 million for farmers.

And North Carolina is on a mission to become the “Napa Valley” of oysters by restoring coastal environments for wild oysters to flourish and by encouraging more oyster farming.

With its roughly 110 miles of coastline, Georgia could one day see this same level of success, but Gallant said to not expect to see any changes soon in Georgia’s oyster industry.

“A law gets passed, but how that law actually functions is figured out after that by the people who implement the law—the regulators. They’re taking their time on that,” Gallant said. “I wouldn’t expect any big news this year.”

Like other agricultural commodities, oysters are not immune to sudden environmental changes. Just as drought can devastate a pecan orchard or a field of cotton, oyster farms can be destroyed by extreme storms, and their habitat is threatened by coastline development, Gallant said.

But oysters offer the opportunity for the state to cash in on a new industry, one that can benefit both our coastal shorelines and the people who live there.

“It provides delicious, sustainable food, and I just wish the government would get on board,” Brendel said.

Jordan Meaker is a senior studying journalism and international affairs at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (0)