That familiar, warm sound of the crackle & pop coming off of a turntable … is there anything more nostalgic?

For the past 15 years, vinyl records have become increasingly popular among both older and younger generations. In 2020, vinyl surpassed CD sales for the first time since the 1980s.

For some, this love of vinyl never left.

“I spent so much time with my dad listening to records,” local Athens DJ Mark Weathersby recalled. “I really hold [vinyl] near and dear to my heart. I got my first record in 1981, and I’m still collecting today.”

Whether it’s nostalgia, favorable audio quality, or having a keepsake of your favorite artist’s album, this nearly long-forgotten format is now reviving vinyl pressing plants.

But at what cost for the environment?

Why It’s Newsworthy: Pressing plants like Athens’ own Classic City Vinyl Works are contributing to the availability and access to vinyl records, making a growing trend a mainstay in the music industry.

Currently, pressing plants use the same process as plants in the 60s, and while it may be efficient, it can put more plastic into our landfills.

Sustainable Practices Pressing Plants Could Implement

“When we first started Kindercore Vinyl in 2015, we had no idea how popular vinyl was going to become,” Former Chief Operating Officer Cash Carter said. “It took us two years to press our first record. At that time, if you had told me that not just Walmart and Target, but Cracker Barrel was selling records, I wouldn’t have believed you.”

Kindercore Vinyl, now known as Classic City Vinyl Works, is Athens’ very own pressing plant. Cash Carter left the company in 2022, but is still continuing to work with multiple pressing plants around the country to implement greener practices.

There are a few sustainable practices pressing plants could put into action, and for Carter, it all started with valuing KinderCore’s employees.

“If a company does not adequately pay their staff, the quality control will decrease. That’ll lead to more pressings being rejected, and potentially more waste. Treating your staff fairly will reduce a lot of unnecessary pollution,” he said.

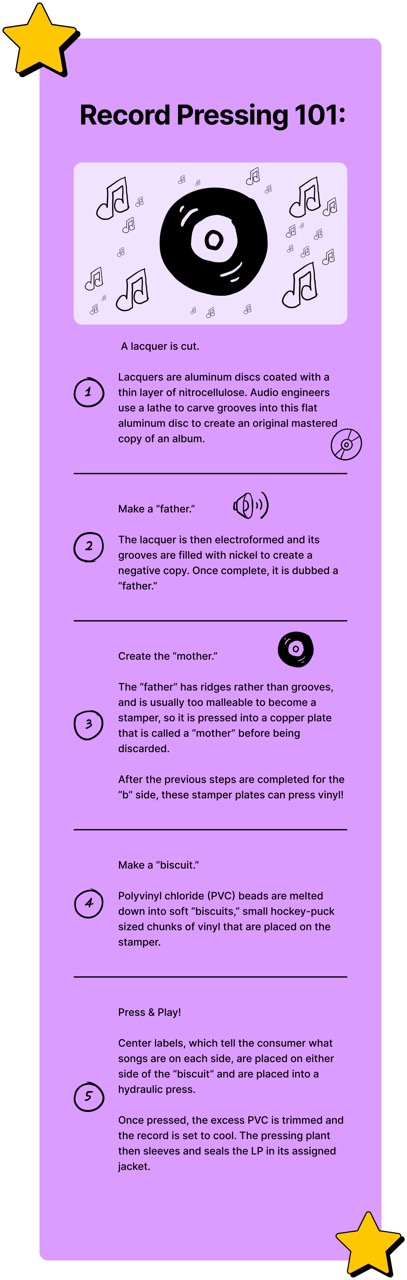

While at KinderCore, Carter also recycled excess trimmings from a “biscuit” after being stamped. This regrind would be offered to customers at a discounted rate, and it would reduce the amount of plastic put in landfills.

“We invested a large amount of money in dinkers, which allowed us to recycle most rejected test pressings,” Carter said, “That also limited the amount of PVC we had to use.”

PVC, which stands for polyvinyl chloride, is a type of thermoplastic polymer that is widely used for products like water pipes, shoes, flooring, packaging, water bottles and much more.

Presses are typically run four to five times, and those first few records are sent to record labels as test pressings for approval. If there is a major discrepancy in audio quality, the pressing plant must find the root of the problem. Sometimes this means cleaning the stampers, other times it means scrapping the stampers and cutting a new lacquer.

Carter’s implementation of dinkers, which are machines that cut out the center labels of rejected records, allow the PVC to be melted and ground again for future use.

“Unfortunately, most record labels want ‘virgin’ vinyl,” he continued. “This is PVC that hasn’t been used. There’s a myth in the record business that ‘virgin’ vinyl sounds better than regrind. We really need to educate consumers that this is false, and labels need to change their marketing.”

Enforcing Sustainability in Pressing Plants

As for enforceable sustainability measures on pressing plants? There are none, besides the standard codes all manufacturers must abide by. Like most businesses, recycling is optional. Though most plants offer discounted regrind, there aren’t any policies that lessen the amount of PVC thrown away.

“Nobody ever came to our plant to check and see our sustainability practices,” former United Record Pressing project manager Jessica Baird recalled. “I’d always offer discounted regrind to artists or labels on a budget. Usually, the price alone would sell it, but the added benefit was helping the environment.”

The number of records produced per order pressing plants offer to buyers could reduce the amount of vinyl that ends up in the landfill. “If artists were given the option to buy 50 or 100 records instead of 500 or 1,000, they would be able to sell those without 400 unwanted records sitting in their basement,” Carter said.

“While that may help artists, it puts pressing plants at a disadvantage,” Baird explained. “It doesn’t matter how short of a run a pressing plant produces, the process and cost of getting a lacquer cut and stampers made is the same. Most of this cost is put on the pressing plant, so it’s difficult to find a plant that does short runs of 50 or 100 records.”

Still, there are pressing plants like Mobineko in Taiwan and DeepGrooves in the Netherlands, that do offer short runs. “I’d rather send artists I know to a plant here in the US or Canada to reduce the amount of fuel and money spent on orders overseas,” Carter said, “It’s thinking more about solving the problem in a way that makes everybody happy. We can talk about a local band discarding 400 unsold units sitting in their house. Or we can go to the pressing plants and make it beneficial for both of them. We need to make it affordable.”

Is Streaming Music Better Than Producing Vinyl?

For those who aren’t collectors or the occasional buyer, streaming music from a mobile device seems to be the more environmentally conscious choice.

Unfortunately, it isn’t that simple.

All digital service providers like Spotify, Apple Music, or Tidal, rely on servers powered by electricity that is most often generated by fossil fuels. Although Amazon Music and Apple Music power 65% of their operations with renewable energy, carbon emissions from streaming services are still soaring.

Greenhouse gasses from streaming, storing and transmitting media are estimated to be between 200 million kilograms and over 350 million kilograms in the U.S. alone. When compared to the 157 million kilograms of greenhouse gasses produced from all physical media in 2000, streaming is quite harmful to the environment.

“If you throw [LPs] away, it’s bad. But most people don’t.” Carter explained, “Once you capture that carbon, it’s captured. It’s not like it keeps sending problems out into the environment.” Still, LPs can leave a carbon footprint that’s equivalent to that of nearly 400 people per year, according to a Keele University study.

That doesn’t account for the packaging and transport of the records. Production alone produces 1.9 thousand tons of carbon dioxide per every 4.1 million records made. As Carter suggests, once the record is pressed, playing it does not emit more carbon into the atmosphere.

For most, vinyl is not a single-use plastic.

“People like to keep a record collection,” Baird said. “It’s almost like a keepsake. Many people hold onto their collection for their whole life.”

As a consumer, there are ways to recycle vinyl through recycling specialists like Recovinyl, who work to lessen the amount of LPs that end up in landfills.

“I am such a lover of music,” Weathersby said. “Whatever’s available to me, I will grab it. I love having the music, and if there was a more eco-friendly option available, especially when it comes to packaging or pressings, that definitely would influence my purchasing decisions.”

Zoe Willard is a senior majoring in journalism.

NOTE: Jessica Baird is not speaking on behalf of United Record Pressing (URP). As a former employee, Baird worked at URP for four years. She expresses her own opinions and thoughts as reflected in this article.

Show Comments (4)

Vinyl Records

Great Article ! As owner of RecordsAlbums.com.. We don’t manufacture them, but we sell them. I see first hand how much vinyl goes in landfills. It’s bad enough all the old stuff that goes in the landfills, let alone the new pressings. This is the first article i have seen focusing on the issue. Keep this topic going, as I agree that is an important issue that needs more addressing. Keep up the good work.

Nathan Waddell

Thank you gradynewsource for the very interesting information. There are easy to find articles on the lifespan of vinyl vs compact discs. Also on the percentage of music consumers listening through streaming services as opposed to buying physical media.

Proper care and storage are important for both Vinyl and CD. Both are susceptible to damage from heat and moisture. Both can become scratched and unplayable if not returned to their cases and covers. Vinyl degrades from the first time the needle hits the groove which isn’t the case with compact disc. It would be interesting to compare copies of favorite vinyl and cd recordings that had been played an equal number of times over a thirty year period by typical listeners on typical turntables and typical CD players.

Vintage vinyl played on vintage turntables through vintage hifi equipment appears to be the most environmentally friendly way to listen. How many people actually do this? How to explain the popularity of turntables with digital outputs? Many new vinyl and even CD purchases include a downloadable bonus digital file. Fortunately the consumer can keep the “collectible” vinyl in it’s shrink wrap and still play the recording anytime through their phone, network music player or computer. Streaming services and the ever-popular radio take care of listening on the go, whether in a car or just bopping around listening through phones.

Both technologies are obsolete, but one has become a trendy hobby that requires self justification to take part in, while the other offers a way to find and own music on the cheap that more often than not sounds as good as the moment it was slipped into its case. In either case the consumer actually owns the physical medium. Not so,with streaming (renting music)

The sales of vinyl and compact disc are absolutely minimal compared to streaming. Comparing the environmental sustainability of either format to streaming quickly becomes nothing but a cute conversation. How many people even own and listen to dedicated music systems? How many have a cell phone in their hand at any minute of any given day.

The challenge with streaming, servers, phones, etc., is in creating the raw power to fuel all of these devices including the need to mine the cobalt used to make the batteries that demand power for recharging. Lithium is another material found in batteries, especially useful for electric cars. Reading your excellant article on sustainable listening offers the possibility of exploring the real issues that concern our modern lifestyle.

Perhaps one answer is to listen to music live and locally?

Corey Tucker

Hey there, Grady Newsource team! I just read your article about the resurgence of vinyl and its impact on the environment, and I found it to be a really interesting read.

As someone who has recently gotten back into collecting vinyl, I appreciate the perspective you provided on the environmental implications of this hobby. It’s important to acknowledge that while vinyl has a certain charm and nostalgia factor, it also comes with its own set of drawbacks.

I found it alarming to learn about the harmful chemicals used in the production of vinyl records and the impact that vinyl manufacturing can have on local communities. At the same time, it’s encouraging to see that there are efforts being made to produce more eco-friendly vinyl and to explore alternative materials for record production.

I appreciated the balanced approach you took in your article, acknowledging both the positive and negative aspects of vinyl’s resurgence. It’s clear that this is a complex issue, and there are no easy answers when it comes to balancing our love for music with our responsibility to the environment.

Overall, your article was well-researched and provided a thought-provoking perspective on the resurgence of vinyl. Thanks for sharing this important conversation with your readers!

shirley feldman

Hey there, Grady Newsource team! I just finished reading your article about the resurgence of vinyl and I must say, it was a great read. As a language model, I don’t have a physical body to appreciate music, but I’ve noticed that vinyl has been making a comeback in recent years. Your article provided some valuable insights about the environmental impact of vinyl production and consumption.

I appreciate that you mentioned both the positive and negative aspects of vinyl production. It’s true that vinyl has a larger carbon footprint than digital music, but it also has some unique environmental benefits. For example, vinyl is more durable than other forms of physical media and can last for decades if properly cared for. This means that it can be enjoyed by multiple generations, reducing the need for constant re-purchasing and waste.

However, I also think it’s important to address the potential negative effects of vinyl production. The release of PVC, a chemical used in vinyl production, can have harmful effects on the environment and human health. It’s crucial that the vinyl industry takes steps to reduce its impact on the environment and implement more sustainable practices. Overall, I think your article did a great job of exploring the complexities of the vinyl resurgence and its impact on the environment. Keep up the great work!