Athens residents could be removed from registration rolls if they have not voted in recent elections and do not confirm their residency.

Why It’s Newsworthy: Inactive voters in Athens will be removed from registration rolls in 2019.

If removed, they will be unable to vote in elections after the upcoming midterm elections on Nov. 6, 2018.

Cora Wright, elections assistant at the Athens-Clarke County Board of Elections, says voters who do not exercise their rights within three years are listed as inactive voters. Voters have the next four years to vote before the Board of Elections mails them a notice warning them they will be purged from the election rolls.

“Anytime we purge, it’s always the odd-numbered year,” she explains. “We don’t do it on election year.”

The “use it or lose it” approach could also affect voters who have already been purged. They could show up to polls during the general election only to find that they are no longer registered to vote.

Wright says she is also obligated by law to automatically purge voters who are deceased, convicted felons, or request removal from the voter roll. She then notifies them by mail of their removal.

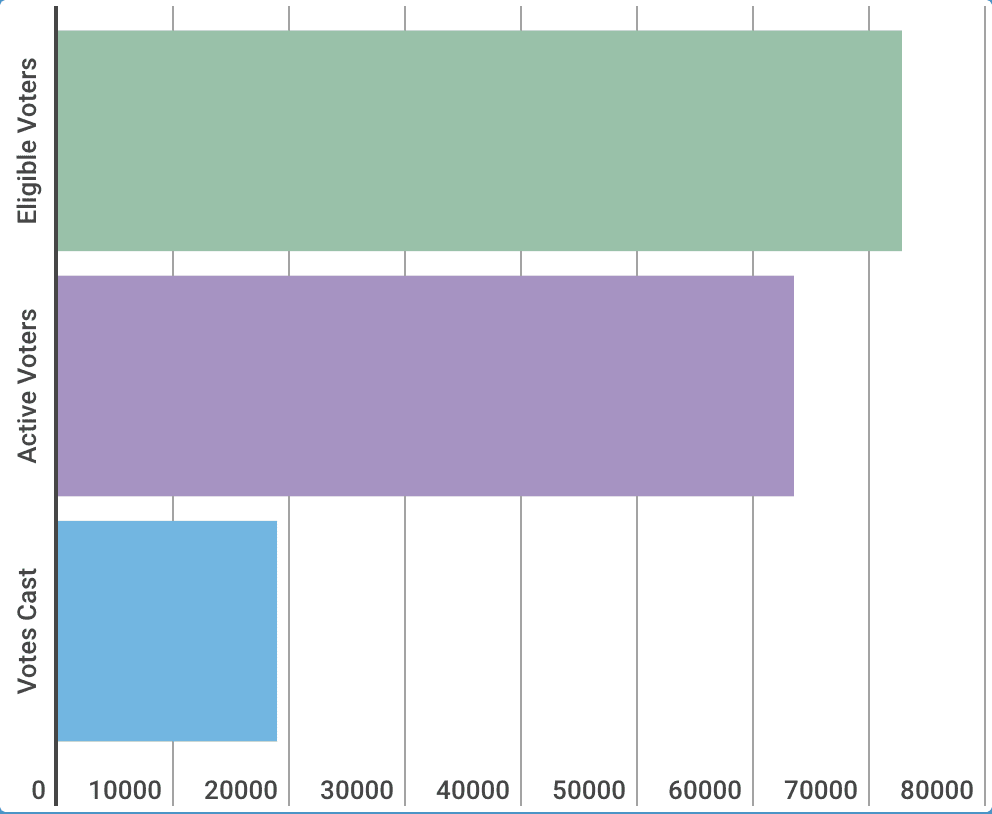

Athens-Clarke County Unified Government reports there are 72,753 eligible voters but more than 9,000 fewer active voters on file as of January 2018. Purges may not legally take place within 90 days of an election, but with only 63,439 active voters on file, that means the Athens-Clarke County Board of Elections will mail more than 9,314 Athens voters notices warning they will be purged from the rolls if they do not vote in November.

Brian Kemp, Georgia’s Secretary of State and now the 2018 Republican candidate for governor, spearheads the state policy that requires removing inactive voters from registration rolls after seven years. For years, opponents have accused Kemp of committing voter suppression while in office.

“I was elected as Georgia’s Secretary of State to ensure secure, accessible and fair elections,” Kemp said in a statement in 2017. “I will never retreat from that constitutional duty and obligation.”

A study from the Brennan Center for Justice, however, shows that states with a history of racial discrimination are more likely to purge voters. It has found that between 2012-2016, nearly 1.5 million voters were removed in the state of Georgia.

Groups such as the American Civil Liberties Union have pushed back against this policy to no avail. The U.S. Supreme Court recently dismissed the case, citing a similar ruling in Ohio.

Despite accusations, the secretary of state has not been formally investigated for voter suppression during his eight-year tenure due to lack of evidence. By law, purges typically come from local boards of elections, not the office of the secretary of state.

“I trust that [Kemp] would do the right thing by the people. I trust that,” Wright states. “But if something comes across our desk that seems unusual, we make contact [with voters] before going any further.”

Residents are also still able to re-register to vote if they have been removed from registration rolls. Prospective voters must register online or in-person with their local boards of elections within their voting district.

The graph below compares the stark contrast between the number of both eligible and active registered voters in Athens-Clarke County versus the number of votes tallied during the May 2018 primary election. But if voters are removed after the general election, the gap between the number of eligible voters and the number of votes tallied could become much smaller.

Mae Eldahshoury is a senior majoring in journalism.