If you’ve lived in the state of Georgia, more than likely you are familiar with the concept of “the Georgia peach.” It’s on the welcome sign at the border, on licence plates and part of the state’s official logo.

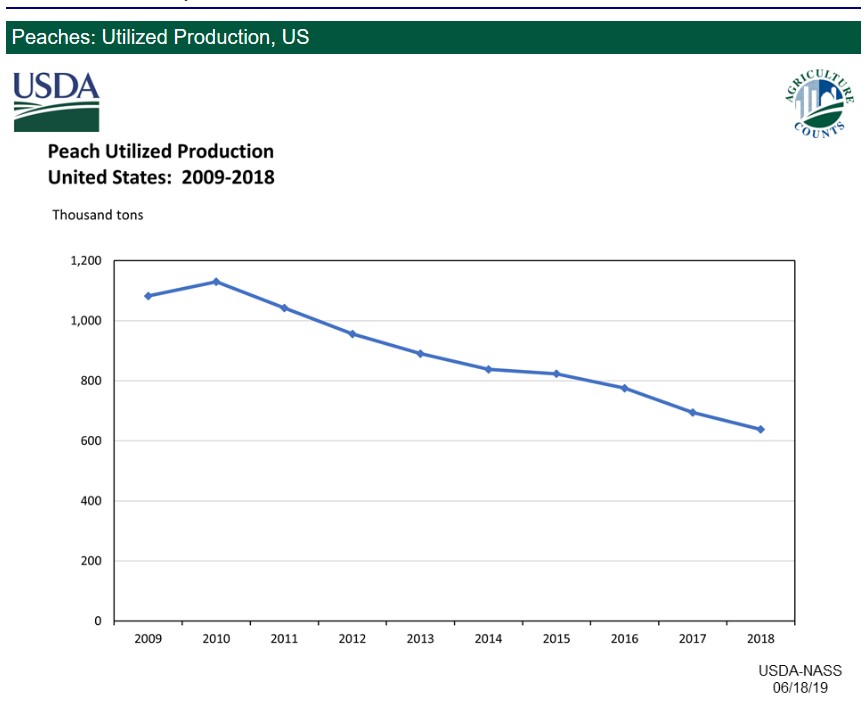

According to USDA statistics, however, the overall utilized production of peaches has been on a gradual decline since 2009. In 2018, the amount of acres bearing peach trees was at 74,500, in contrast to 102,540 acres in 2014. Reasons for this decline are not clear according to statistics alone; historically, farmers encounter a variety of threats to their crops and production in the form of deadly diseases and unpredictable weather patterns.

Reasons for this decline are not clear according to statistics alone; historically, farmers encounter a variety of threats to their crops and production in the form of deadly diseases and unpredictable weather patterns.

For the last 30 years, according to Guido Schnabel, a researcher and plant pathologist at Clemson University, a disease known as armillaria root rot (or oak root rot) has taken center stage as the primary obstacle to peach growers in the southeastern states. Armillaria is, according to Schnabel, a “deadly” threat to peach growers in Georgia and South Carolina, which are among the top four peach growing states in the country. In the state of Georgia, peach trees that get harvested make up 10,000 acres alone.

For Georgia farmer Lawton Pearson, the newest measures to protect against armillaria diseases have come early enough to protect the future of his orchards. For others like Jerry Thomas, the solutions came too late.

Why It’s Newsworthy: Armillaria root rot, also known as oak root rot, has the potential to significantly impact the southeastern peach crop if farmers do not change their planting strategy. However, protective planting or grafting measures against armillaria are sometimes costly and time-consuming to the farmer who deals directly with this disease, creating the potential for vulnerability in the future of the peach crop. Some farmers have already lost their orchards to this disease.

The Disease

Armillaria root rot is a fungal disease that can affect many different varieties of tree, but is particularly deadly to peach trees. The disease spreads through old, decaying roots that are left in the soil from previous root systems. These residual pieces of root can carry the disease but can also lay dormant for years on end, adding a facet of unpredictability to it.

“This is a major threat to the peach growers, and the reason is that it will just get worse over time. A grower only has only so much land available, and eventually all those lots and all those fields will accumulate enough root pieces that will then impact the new crop, and so at year three, four and five, just when the new crop is about to hit full production, you’re going to see 30, 40, 50 percent tree decline on such really bad sites, and that is just not something a grower can withstand. That is just, deadly,” said Schnabel.

Schnabel asserts that the disease, though slow-moving, is very potent. The more the land has been reused, the more likely a farmer can be to experience armillaria. The problem is less having to do with soil being recycled, but the accumulation of infected roots over time. Peach farmers are limited in their ability to plant the trees anywhere they want, having to be sensitive to climate and soil conditions.

Armillaria has not necessarily become more prevalent over time, according to Schnabel. It wasn’t noticed as much in the 70s and 80s when a disease known as Peach Tree Short Life was running rampant, but now that that disease is under control, armillaria root rot has become the primary disease that peach farmers combat.

‘A Circle of Death’

Philip Brannen, a plant pathologist at the University of Georgia, describes the effect of armillaria in an orchard as “a circle of death.”

A characteristic of the disease is for one tree to become infected and for the disease to then spread to the surrounding trees, eventually infecting the entire orchard if the contaminated trees are not removed quickly and thoroughly.

“Some areas have been planted with peaches for probably a 100 years or more, and that pathogen just keeps on expanding its range basically. So, it’s not anything new at all; it’s just the fact that if you’re limited by land and you want to plant peaches, and go back with peaches over and over and over, every time you plant you are going to lose more trees more rapidly, and eventually it becomes economically nonviable,” said Brannen.

Jerry Thomas, owner of Thomas Orchards near Watkinsville, Georgia for 47 years, experienced the deadly effects of armillaria on his orchard.

Thomas likened receiving the diagnosis of armillaria as being told they have “stage 4 cancer.” They attempted to plant peach trees in different locations, with the help of information from the UGA Research Extension, but at the time of the diagnosis of his orchard, it was essentially too late to save it. In 2017, they had their last harvest of peaches. After years of growing peaches, the loss of his orchard resulted in financial difficulties but also signaled the end of a generational practice.

The way forward for Thomas has been sourcing peaches from neighboring farms. He now purchases his from Jaemor Farms, ensuring his customers are still able to buy peaches from his nursery. Though Thomas has felt optimistic about the changes they have made to their business model, he also recognizes that the loss of his orchard has also chipped away at its identity.

“It’s been pretty hard all over, to let that go,” he said.

Brannen, who worked with Thomas during the time in which he realized he had armillaria in his orchard, affirmed its deadly nature.

“Eventually, at some point, if we don’t have a solution to armillaria, it’s going to be very difficult to grow peaches, in Georgia and really, the southeast as a whole,” Brannen said.

Possible Solutions

Still, the light at the end of the tunnel, according to Schnabel, could exist. A rootstock called MP-29, created by Tom Beckman at the USDA, has shown signs of resistance to the disease. In addition, Schnabel has come up with a system known as “berming.”

A berm is a mound of dirt created by the farmer, which becomes the planting site for the peach tree, keeping farther above ground than normal and hopefully away from decaying root pieces in the soil. Though infection with armillaria in most cases will be unavoidable, slowing down the process can allow for farmers to still experience successful yield from their peach trees for a longer amount of time.

Peach trees generally live for 12 to 15 years; those that have contracted armillaria can die after just five years. The video below is an illustration of how armillaria spreads through leftover roots in the soil below a given peach orchard and how Schnabel’s planting method known as “above ground root cover excavation” or berming, can slow down the infection process of peach trees. Planting this way can delay the disease progression by three to four years, allowing peach farmers to garner at least two additional harvesting seasons:

Solutions at Work

In Fort Valley, Georgia, Lawton Pearson, a fifth-generation farmer, has been forcefully combatting armillaria in his own orchards. Pearson Farms is a 1,700-acre farming space with orchards at various growing stages that span across three counties. About six to eight years ago, according to Pearson, he and his farm hands began aggressively trying to combat the disease after realizing they were dealing with armillaria.

Pearson was losing trees after eight and nine years, which is in some cases less than half the amount of time a peach tree is supposed to live. The “unkillable” nature of armillaria makes it a force to be reckoned with, but Pearson and his employees have been using a combination of methods to ward it off.

When you’re dealing with old peach dirt, you have to throw the book at it,” Pearson said.

According to Pearson, himself and his farm hands began quickly pushing out stumps as soon as the trees died to avoid any possibility of rotting pieces getting left behind. Removing dead trees while they are still green is one significant way that Pearson says that they have been able to avoid the infection; the longer the stump is left in the ground, the higher the likelihood that it will leave decaying particles behind when it is pulled out.

In addition, they plant every peach tree by hand, planting them 6 to 8 inches above normal ground using Schnabel’s berming method. The downside to planting by hand, as opposed to using a tree transplanter or heavy machinery that they would normally use to push up an orchard, is that it is a significant time cost.

Between pushing out stumps, berming and now using MP-29 on some of his trees, Pearson has seen encouraging results. He estimates that his farm sells at least 47 million peaches during a given peach season. However, though he has seen success with these methods, the need to be vigilant against armillaria remains.

“It is undefeated. But you can play a better game and you’re just hoping to get enough time; it’s going to win eventually, but you want to win enough battles that you get the profitability of your orchard established,” he said. “So far, everything we have done has helped.”

Sarah Freund is a senior majoring in Journalism at the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at The University of Georgia.

Show Comments (0)