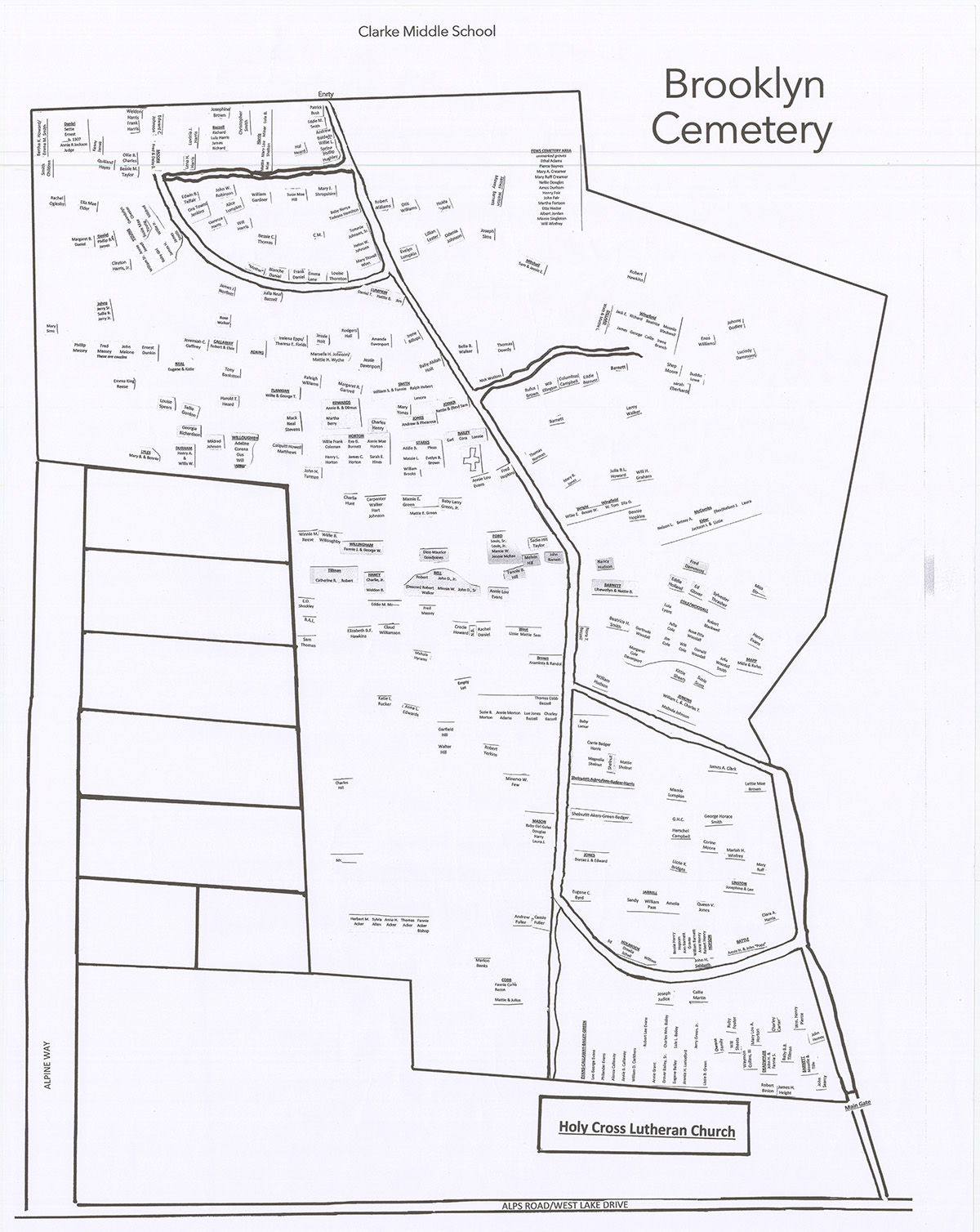

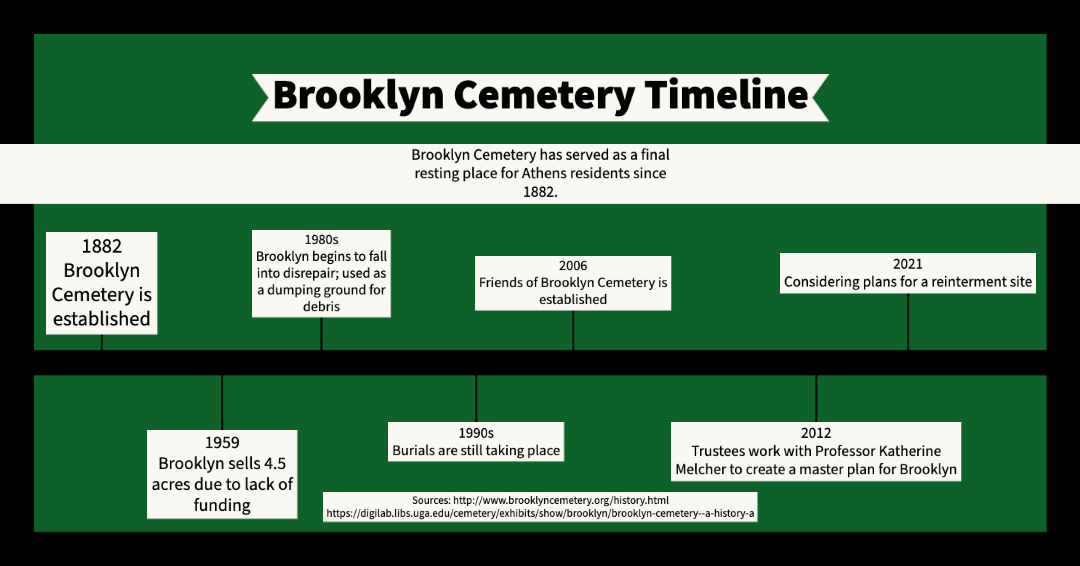

Brooklyn Cemetery is a historically Black cemetery in Athens, Georgia, spanning almost 10 acres. It is bordered by Holy Cross Lutheran Church and Clarke Middle School. Brooklyn was established in 1882 but fell into disrepair around the 1980s.

Brooklyn Cemetery holds a special place in Karl Scott’s heart. He used to cut through it as a kid, and he saw how overgrown it had gotten once he started teaching at Clarke Middle School in the early 2000s.

“I was really shocked at how overgrown it’d become. It was almost impenetrable… It was like going through a jungle,” Scott said.

He would go on to help form Friends of Brooklyn Cemetery right in his classroom in 2006 to clean up the forgotten grounds. Brooklyn is overseen by a board of trustees, but the Friends coordinate cleanup work.

While it is important that Brooklyn is being restored, it is equally important to understand the underlying systems that allowed sacred ground to become a dumping ground.

The Black community, 29.3% of Clarke County’s population, lacks a voice in Athens. Alvin Sheats, president of the Athens NAACP chapter, said there is friction between the Black community and local government, saying the government merely tolerates their concerns.

This community relationship set the backdrop for Brooklyn’s fall into disrepair.

Why It’s Newsworthy: Brooklyn Cemetery’s fall into disrepair illustrates the relationship between the local government and Black community. The effort to restore Brooklyn explains the desire to reclaim the space for the Black community and bring awareness to the importance of Black history.

A Personal Connection

Linda Davis, one of the founding members of Friends of Brooklyn Cemetery, has an intimate connection to Brooklyn.

She knows her grandparents are buried somewhere in Brooklyn, but she can’t remember where, and the markers they once had are gone.

She often wanders through the cemetery, identifying graves for local residents who contact her about their family trees. She is at peace in Brooklyn but never stays still too long, always moving along the path toward her next venture.

Although Brooklyn is her passion project, Davis emphasized the importance of understanding the full story and confronting some of the deeply entrenched systems that allowed for its disrepair.

“I have some foundational beliefs that when we confront ourselves, and when we actually get comfortable in our own skin, as to who we are, then some things will change,” Davis said.

Uncovering History

It is the dedicated work of volunteers like Annette Hatton and Meriwether Rhodes that helps bring out Brooklyn’s beauty and history.

Hatton, a longtime volunteer, started working with Brooklyn several years ago at one of their annual Martin Luther King Jr. Day cleanups. She now serves as a crew leader when other groups from the community come to work.

Hatton remembers earlier cleanups when the stubborn, thick privet grew into towering shrubs, looming over two stories tall in spots. Now, maintenance projects don’t feel as daunting.

“We’ve been able to accomplish so much,” Hatton said.

Rhodes happened across the cemetery upon moving to Athens, and the history piqued her interest. She found records at funeral homes and the Athens-Clarke County Library. Rhodes has recorded over 1,100 graves and believes there are at least 200 more to discover.

She recounted the early days of discovery when she would test the density of the ground by staking a screwdriver into parts. If the land gave away, she knew it was a likely burial spot.

Rhodes still visits the cemetery to place plastic flowers on graves to provide a touch of tender, love and care.

“I think that’s really nice because it shows anybody who goes in there that somebody cares, and if somebody cares, then other people do too,” Rhodes said.

The Rev. Abraham Mosley, the longtime pastor of Mount Pleasant Baptist Church, presided over the last burial at Brooklyn in the mid 1990s, and even before then, he knew the cemetery needed to be cared for. He spent some of his free time trying to clear a path, but it was too much work for one man.

Fortunately, Mosley was not alone in his quest to restore Brooklyn.

A Community Effort

Many groups spend time at the cemetery to contribute to the restoration effort. Members of the North Oconee High School Beta Club, Holy Cross Lutheran Church and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints are frequent volunteers.

Pastor Nathan Hilkert of Holy Cross Lutheran Church explains the “Christian connection” he feels with the members of Mount Pleasant Baptist Church, many of whom have family members at Brooklyn.

“I would say the overriding value there is for us to be good neighbors and to be more aware of our community,” Hilkert said.

Davis forged a partnership with The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and they have brought in members from their disaster relief crew. This team has the special equipment needed to clear trees and invasive species in a fraction of the time it would take volunteers, allowing them to move ever closer toward the goal of a restored and beautified Brooklyn.

Looking to the Future

Even with all the work that volunteers and Davis have accomplished, their work is far from over, she said. Davis has been working with the landscape architecture department at UGA to decide on a design for a reinterment site at the cemetery. This space would serve as a place for family members to reinter remains that were not originally buried at Brooklyn.

Recent controversy over the discovery of remains at Baldwin Hall has raised the issue for descendants.

“My ancestors that were buried beneath that building have now been reinterred at the feet of the people that owned them, and that just offends me greatly,” Davis said.

Overall, Davis wants Brooklyn to be a place of remembrance and tranquility, a beautiful place that family members can visit in order to honor their loved ones.

“It is a sacred place,” Davis said.

Caroline Kurzawa is a junior majoring in journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication and minoring in women’s studies at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (0)