Since September 2018, the second floor of the Richard B. Russell Special Collections Library at the University of Georgia has been transformed into a sort of shrine for one of the university’s greatest football coaches: Coach Wally Butts.

Jason Hasty, the UGA athletics history specialist, created this exhibit. He looked into each glass case proudly, as he explained where he got each item and the significance it held for Butts.

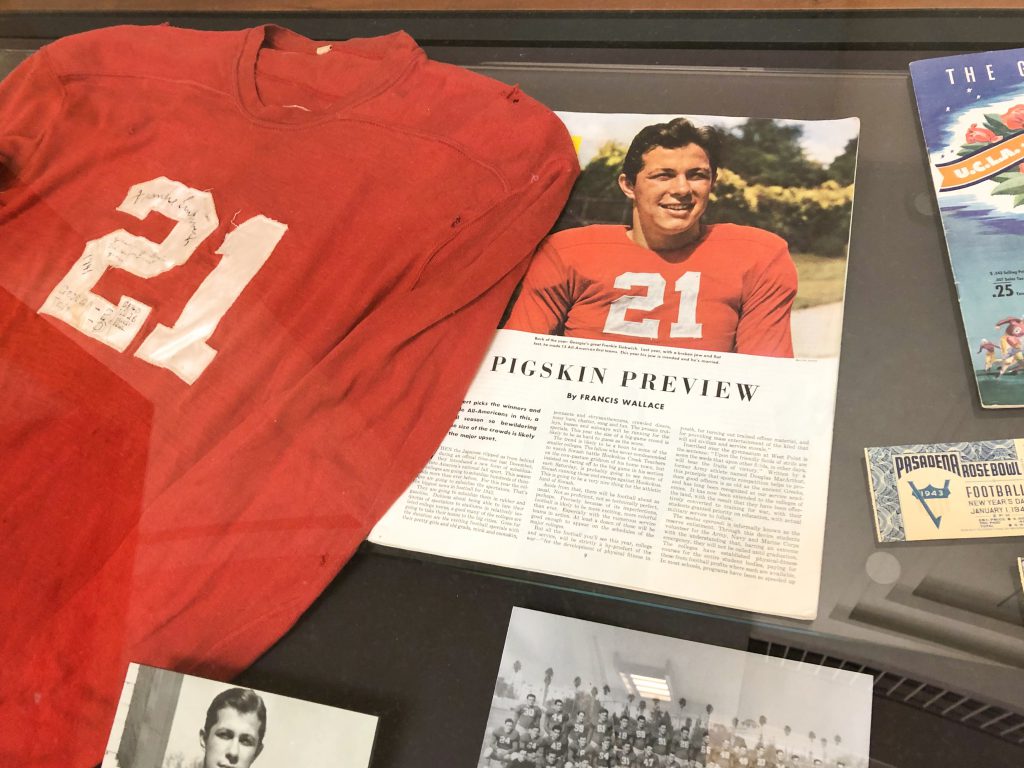

In one case, there were the famous “silver britches” his players wore. In another, there was a shirt signed by numerous players after they won the 1942 Orange Bowl. Another case held memorabilia commemorating one of Butts’ most popular players, Frank Sinkwich.

On the wall, there was a large picture of Butts in his Georgia-red uniform. That same jersey that lay in a case partly covering up the left side of a magazine called the Saturday Evening Post.

It seems like a minor detail, but anyone who knows the history of Wally Butts can see why the The Saturday Evening Post would not be welcome in an exhibit about his life. The 1963 article they published about Butts ultimately ended his career with the University of Georgia.

And in return, he ended the magazine for good.

George Burnett’s Remarkable Story

This year marks 50 years since the Post ran out of money as a result of Butts’ lawsuit against them, a lawsuit in which he claimed that the Post blatantly lied about him in order to harm his reputation.

There are lessons that can be learned from the tale, as now, five decades later, media distrust still runs deep in the minds of many Americans. In a 2018 Gallup and Knight Foundation survey, 69% of American adults said that their trust in the media had declined over the past ten years. When asked to explain why their trust had declined, 45% of respondents cited inaccurate reporting.

As the Butts case reveals, it only takes one major scandal from a publication to potentially bring it down forever.

At the time of the Post’s exposé, the magazine was severely in debt. The publication was already being sued by multiple people who were targets of the publications new investigative reporting style, explained Frank Graham, Jr. in his book A Farewell to Heroes, published in 1981.

If Clay Blair, the Post’s editor-in-chief at the time, was bothered by these suits, he definitely did not show it. Graham recalls a memo Blair sent to many employees at the Post.

“The final yardstick: We have about six lawsuits pending, meaning we are hitting them where it hurts, with solid, meaningful journalism,” Blair wrote, his confidence seemingly unshaken.

Blair coined the term “sophisticated muckraking” to describe the magazine’s new style.

Blair’s savior seemed to be an unassuming insurance salesman named George Burnett, who had approached the magazine with his attorneys to relay an incredible story. As the article tells it, Burnett was placing a call to a friend at an Atlanta public relations firm in the fall of 1962 when his line was mixed up. Instead of being connected to his friend, Burnett heard the operator connecting Coach Wally Butts, then the Athletic Director at UGA, with University of Alabama head football coach Bear Bryant.

This phone call was just days before the 1962 football game between Alabama and Georgia, and throughout the conversation, Burnett says he heard Butts telling Bryant everything he knew about the Georgia team’s plays and players. He was helping Bryant prepare to beat Georgia.

And that is just what happened. Though the betting line initially had Alabama beating Georgia by 7 points in the big game, the Crimson Tide would come to beat the Bulldogs 35-0.

Burnett had taken notes throughout this alleged conversation, and when he handed these notes over to current UGA head coach Johnny Griffith, he set the wheels in motion for an investigation into the two men.

The article claims that Burnett was called into a meeting in his attorney’s office with Bernie Moore, the commissioner of the Southeastern Conference, Dr. Adherhold, the president of UGA, two members of the board of regents and one friend of Coach Butts. When Burnett felt like the conversation was drifting towards questioning him over his past financial issues, he decided he would rather take his story to the Saturday Evening Post.

This story was perfect for the Post. Not only did it fall in line with their new investigative focus, but it would also help them win their already-pending libel case from Bear Bryant.

In October 1962, the magazine published an article by Furman Bisher titled “College Football is Going Berserk,” which outlined all the ways college football coaches, including Bear Bryant, were encouraging unnecessary violence during football games.

Though the premise of the article was not unlike articles published today on concussions and other football-related injuries, Bisher made baseless claims that Bryant was encouraging his players at the University of Alabama to play dirty.

After discussing an incident between an Alabama player and a player on the opposing team, Bisher blamed Bryant for the player’s injuries as much as he blamed the Alabama player.

“[The] coach who encourages or even tolerates a player who violates the spirit of the rules is placing the future of football in jeopardy,” Bisher wrote.

Bisher also quoted Coach Ralph Jordan of Auburn, who claimed that football had gotten more violent because that was the only way to challenge Bryant’s team.

Following the publication of this article, Bryant sued The Post’s parent company, Curtis Publishing, for $500,000.

“When you look at it from the Alabama perspective, you see that The Saturday Evening Post really had a bone to pick with Bear Bryant,” Hasty says. “And I think, unfortunately, Wally Butts got caught up in that to a certain extent.”

A Historic Ruling

Following the release of “The Story of a College Football Fix” by Frank Graham, Jr. in the March 1963 issue of the Saturday Evening Post, Wally Butts and Bear Bryant each sued Curtis Publishing for $10 million.

The coaches argued that the Post had committed libel, meaning they had published an untrue statement in order to harm the coaches’ reputations. Butts had to resign from his position as Athletic Director for UGA following the investigation because, as Hasty said, he did not want to get the university involved with the court proceedings.

After passing through various lower courts in the state of Georgia, Butts’ case ultimately went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Dr. Jonathan Peters, who holds a law degree from the Ohio State University and a doctorate in journalism from the University of Missouri, has a unique interest in the Butts libel case.

Peters, a professor at in the UGA Grady College, points out that just three years before Butts’ case made it to the Supreme Court, a separate case called New York Times v. Sullivan had just been decided. That case set the ground rules for when a story published about a public official constituted libel. According to Peters, the Sullivan case brought forward a whole series of other defamation cases, and the court struggled to figure out a set standard for libel.

“So in Curtis Publishing, [the Supreme Court] eventually reasoned their way into the conclusion that we will use as a fault standard whether the journalist behaved in a ‘highly unreasonable manner,’” Peters said.

In other words, the Supreme Court needed to come up with a universal standard on which to judge a libel case. The standard they came up with during the Butts’ case was similar to what they decided in the Sullivan case: if the journalist behaved unreasonably, then libel was committed.

However, just 10 years later, the Court abandoned that approach and decided that the plaintiffs must prove “actual malice,” a standard that is much harder to prove than the previous unreasonable manner standard, Peters explained.

If Butts v. Curtis Publishing had happened under this standard, it is possible Butts could have lost the case. “Now that being said, the facts in Curtis Publishing are pretty bad on the part of the Post. It behaved really poorly by its own admission,” Peters said.

But just what exactly did the Post admit to?

In the final chapters of his book, Graham goes into great detail about how he got the information for the article and how he wrote it. Many of his actions would largely be frowned upon by journalists and media experts today.

“As in a classic disaster,” Graham, Jr. wrote, “the wheels, once set into motion, could not be stopped.”

For one thing, Graham Jr. stated that the Post paid Burnett $5,000 for his story, a sum that could really help an insurance man with money troubles.

He also wrote that during his meeting with Burnett, they were only able to record half of the interview before his fellow colleagues had to fly back to New York, and the tapes had to be sent to them as soon as Graham, Jr. left the interview. Because he thought he would have access to the tapes, Graham, Jr. did not take very many notes, so his article mostly relied on his memory and half of his notes.

Finally, Graham, Jr. admitted that he had merely “reconstructed” certain quotes from his article instead of getting information straight from the people who quoted

This last point was especially helpful for Butts’ case, and even Graham, Jr. admits he thought this fact lost them the trial.

The $3,060,000 in damages awarded to Butts was one of the largest libel awards at that time, and though it was later reduced, Curtis Publishing could never recover.

Dr. Sonja West, a Constitutional Law professor at UGA reflected on this situation and put it this way: “It’s the case that really sort of ended The Saturday Evening Post.”

Lessons from the Post’s Playbook

In 2013, on the 50th year anniversary of the publication of “The Story of a College Football Fix,” the Saturday Evening Post, now just a website with archives online articles, looked back on Butts v. Curtis publishing and the mistakes that they made.

However, these reflections were not admissions of ethical journalistic errors. Instead, they included excuses such as the Post hired a bad lawyer and that the Post editors did not attend the trial. Additionally, the article claims that Alabama football players allegedly taunted Georgia football players with the names of their own plays when they met in 1962, a fact that Hasty says is merely a rumor.

Ultimately, the Post still maintains that it was wronged in this case.

In the 80 years since Wally Butts began his career as head coach at UGA and the 50 years since the Saturday Evening Post printed its final pages, a lot has changed in the field of journalism.

Public figures and the media have sparred numerous times since 1939, but some could argue that it has never been quite as bad as it is today. In 2019, public officials are able to decry the media through social media as well as in the press, and “alternative facts” have embedded themselves into the rhetoric of our society.

To top off these verbal attacks, newspaper and magazine subscription rates have been on a steady decline. In a recent Pew Research Center survey, only 13 percent of American adults preferred to get their news from newspapers, and only 14 percent have paid for local news in the past year.

Getting the facts right and relying on research and facts to back up breaking news is incredibly important to maintaining the strength and reputation of the news industry.

Wally Butts’ lawsuit, though devastating for the Saturday Evening Post, did not devastate the entire journalism profession. In the previously-mentioned Knight Foundation survey, 69% of Americans stated that they felt that their trust in the media could be restored.

But restoring it will require some work. This case ultimately serves as a reminder for journalists to do their homework, check their sources and stick to reporting the truth instead of the most eye-catching story.

Morgan H. Frey is a graduate student working towards a master’s degree in journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia.