If it’s a sunny day, expect to find the greater population of Copenhagen outside, trading phones and laptops for conversations over coffee and soaking in the warm weather.

On days like this, green spaces like local farms become oases for the Danes to escape from the bustle of life in the city to enjoy time spent amongst the greenery, connecting themselves to the earth.

Denmark has seen a rise in the popularity of these urban farms in recent years, due to both a rise in urbanization and a desire to be more sustainable.

Why It’s Newsworthy: The urban farming industry has been expanding over the past decade, not just in Denmark, but in developed economies all over the globe, creating the diversity in food production necessary to reflect the constantly changing climate.Why Farm Locally?

Urban farming is the practice of growing organic produce in cities by using the city itself, the people, existing architecture and food waste, as a resource in the produce cultivation.

Growing produce locally increases the accessibility of fresh fruits and vegetables and enables farmers to reuse and reduce waste from the city. Sludge and city water can be used as fertilizer as well as existing food waste like coffee grounds.

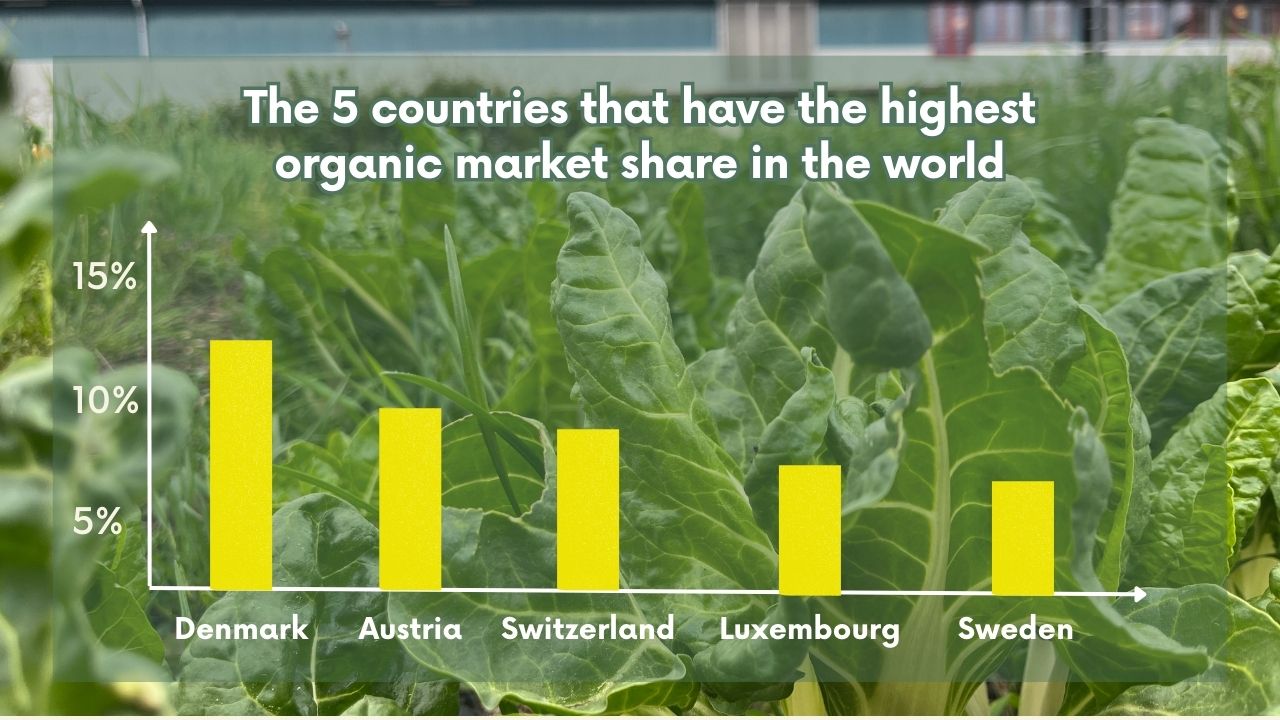

There is a strong emphasis in Denmark placed on buying organic produce, and according to the World Agriculture Report of 2021, the Danes consume the most organic food per capita than anywhere else in the world and have the highest organic market share at 12.8% in 2020.

However in Copenhagen, Denmark, urban farming is not only about making produce more accessible, it’s about engaging the community by bringing people together and raising awareness about where their food comes from.

Kristian Laursen, an associate professor in urban agriculture at the University of Copenhagen, says one of the most important parts of urban farming is getting people interested in where their food comes from, which in turn encourages them to engage in sustainable practices, such as cooking more efficiently to avoid food waste and buying and trading locally.

“Community gardening and people getting together producing the food and eating and so on, the social aspect of urban farming is extremely important. And in some parts of the world, I would say it’s much more important than the actual production,” said Laursen.

At the urban farm ØsterGro, this is one of their core values.

Involving the Community

ØsterGro is a small farm situated on the rooftop of an old car auction house in Copenhagen’s first climate resilient neighborhood, Osterbro, and boasts to be Denmark’s first rooftop farm, opening up in 2014.

The farm is open to the public and welcomes anyone to hang out in the garden as an escape from the bustle of the city below. The rooftop is also home to Gro Spiseri, a communal style restaurant that also functions as a greenhouse.

During the week, farm manager Nanna Jespersen can be seen around the farm, tending to her produce and feeding leftover weeds and food waste from the restaurant to her chickens.

Jespersen started as the farm manager in March of 2022, coming straight from a normal desk job. She now says that she’s extremely happy to be part of something that she knows is actively helping the community and the environment.

“I feel very fortunate to be here and to be doing something very meaningful in the sense that, once you live in the city, we all miss that connection to where our food comes from,” said Jespersen.

ØsterGro operates as Community-Supported Agriculture, a model based off of a United States concept. They have a community of 40 members who pay in advance of the season to receive bags of produce put together by Jespersen that are picked up throughout the growing season, giving these families an intimate connection to their food and the growers.

These CSA members often stay with the farm from season to season, creating a deep bond but also a level of exclusivity amongst them.

Jespersen says it is unrealistic to aim to feed the entire city because their small, 600-square-meter roof only holds 250 square meters of garden beds, so they try to find other ways to engage the greater community of Copenhagen.

They hold workshops and invite kindergarteners for sessions to learn about food production and small scale farming, as well as hold volunteer days every week where anyone, local or not, can come help tend to the garden, creating friendships and a connection to the farm.

Fostering Connection

After eight growing seasons at ØsterGro, their management started Øens Have, another farm with the same aim of making the city greener by bringing fresh food closer to the people.

Here volunteers can also be seen populating the garden on Tuesdays, weeding, planting and feeding snails to the chickens. Many volunteers have been coming every week for many weeks, seeking the bonds created by spending hours in the garden with one another, but there are always some that are new.

Alastair Barron, an exchange student from Scotland, attended only his second volunteer day last week, but he says even though he hardly knows anyone well yet, he feels like he’s a part of the community.

“It’s just so chill. Like, you can just come and then just plant seeds for like hours. It’s just really nice. Nice people. Conversation or not depending if you want to,” said Barron.

Through volunteering he has been able to experience things outside of his sociology studies and has connected with two other exchange students, Frederick Lucas from Belgium and Anna Baechtold from North Carolina.

The Future

Copenhagen is aiming to be the first carbon neutral capital by 2025. There is belief that this goal will not be reached; however, there are hopes for neutrality in the coming decade.

To achieve this, new technology and concepts have been introduced to Denmark in recent years such as vertical farming, a practice that often uses hydroponics to grow produce indoors and in cities year round.

What’s Working

-

Is underground farming the future of food?

There’s a subterranean, organic farm in one of Seoul’s subway stations that could be another way to approach sustainable urban farming. The “vertical” farm, known as Metro Farm, uses a mineral nutrient solution instead of regular soil, and has an automated tech network to control the underground ecosystem’s temperature, humidity, and carbon dioxide levels. While Farm8, the tech startup in charge of the venture, hasn’t made much of a profit yet, the farm produces about 30 kilograms of vegetables per day at a rate that is 40 times more efficient than traditional farming.

The climate is constantly changing and people are always coming up with ideas to become more sustainable and reach this goal of climate neutrality, but Jespersen encourages individuals to be the ones to get out there and actually act on these ideas, rather than wait for others.

“That’s why to me, it feels very nice to be somebody with the shovel in my hand instead of at the desk coming up with the bright idea,” said Jespersen.

Abigail Austin is a senior majoring in journalism at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (0)