When Megan Bocanegra started working as a 911 dispatcher, she expected it to be temporary. She’d just finished her bachelor’s degree at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and debated whether to attend graduate school.

In 2005, she decided to work at the communications center in her hometown of Oxnard, California, and continued working there for the next 11 years.

She enjoyed serving the community she grew up in, but the life of a dispatcher is an endurance test.

Why It’s Newsworthy: 911 dispatchers are the bridge between the public and first-responders. They are responsible for sending help in emergency and non-emergency situations, but the job’s stress leads to high turnover rates.It’s a really tough job. It’s unbelievable,” she said.

The United States has around 95,000 police, fire and ambulance dispatchers throughout the country, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

They handle around 240 million calls in the United States every year, according to National Emergency Number Association (NENA).

Communities in Georgia employ more than 3,000 dispatchers. In Athens-Clarke County, the Central Communications Bureau received 108,830 emergency 911 calls in 2017, the report said.

The Workload

As a dispatcher, Bocanegra routinely worked 10 to 12-hour night shifts. “We were chronically understaffed,” she said.

These long hours are typical. In Athens, dispatchers work from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. or the reverse. They have to work weekends and holidays.

Bocanegra, now 36, also had mandatory overtime shifts.

“We would usually work 60 hours a week with an hour break, if we got lucky, each day,” she said. “It was a big burden.”

The physical and mental toll adds more stress to a job that already handles life and death calls, where the lives of citizens and police officers can depend on the dispatcher.

“You had no idea what was going to be on the other end,” said Bocanegra.

You have to get everything right all the time. There’s no margin for error in that type of job.”

During her shifts, she couldn’t leave her station for more than a few minutes. At any time, calls could flood the center.

“It’s tough because it’s almost like you end up having this nervous energy because you’re not moving,” she said.

“You’re just like sitting there, but there’s so much hyper-stimulating, and you’re physically tethered to a console.”

At Oxnard, she sat at a console, hidden behind nine glowing monitors. The room could only fit seven stations, and it had no windows. After her shifts, she sometimes couldn’t figure out the time of day.

“I don’t even know if its light or dark out. What time is it even?” she said. “It’s sort of disorienting.”

The Emotional Weight

In addition to the job’s demands, dispatchers can experience traumatic calls that impact their emotional well-being.

Nearly one-third of calls produce peritraumatic distress among 911 dispatchers. A study by the Journal of Traumatic Stress linked the distress to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

“I dispatched in the community that I grew up in. Same town,” Bocanegra said. “So I remember a call of a kid, I think she was maybe 14 years old, but found her brother had hung himself from the monkey bars at a park. And it was the park that I had played at when I was a kid.”

She described listening to the girl’s misery while simultaneously imagining that playground. Suicides often made the job difficult because the callers were overcome with hysteria.

One girl called 911 after her boyfriend killed himself with a shotgun. Bocanegra could hardly figure out the girl’s location because of her reaction.

She said that calls involving police officers in danger were particularly taxing. Dispatchers and officers have close work relationships.

“Anytime an officer was getting assaulted or was in trouble that was really tough to listen to in your ear and know that you’re not physically going out to help,” she said. “And you’re kinda powerless to just be sitting behind that computer screen listening to it.”

The trauma study noted that the calls that cause the most peritraumatic distress involved children or first-responders.

It’s that feeling of being like powerless and helpless that really, I would say, was one of the harder things to deal with,” she said.

The Turnover

911 communication centers struggle with turnover rates. The national average turnover rate for dispatchers is between 14 and 17 percent, said Athens-Clarke County Public Information Officer Geoffrey Gilland.

By comparison, the average turnover rate in emergency medical services (EMS) is 10.7 percent, according to a report in the U.S. National Institutes of Health’s National Library of Medicine.

“Our average is less than 7 percent. We have a pretty stable environment,” Gilland said. “It’s pretty amazing.”

While dispatch employment is expected to grow 8 percent by 2026, the Bureau of Labor Statistics said, the majority of these openings come from dispatchers who leave their positions

Bocanegra estimated that three-fourths of potential hires would not proceed past training. She decided to continue out of a sense of duty despite the difficulty.

“I felt that if I wasn’t going to do it, who else was going to? Because I knew that we had so few people anyway,” she said. “Truthfully, personally, I think it was guilt.”

There were also personal reasons that kept her in the position. Her then-husband worked in the department.

“He was a police officer, and I was a dispatcher, so it was almost a watching out for each other,” she said. “I was taking the call, and I was sending him to a call. So I wanted to feel like I knew what was going on.”

Eventually, Bocanegra decided to transfer from dispatch to crime analysis.

I was exhausted,” she said. “I just felt emotionally drained, and I wanted to be able to have a regular job.”

From Dispatch to Analysis

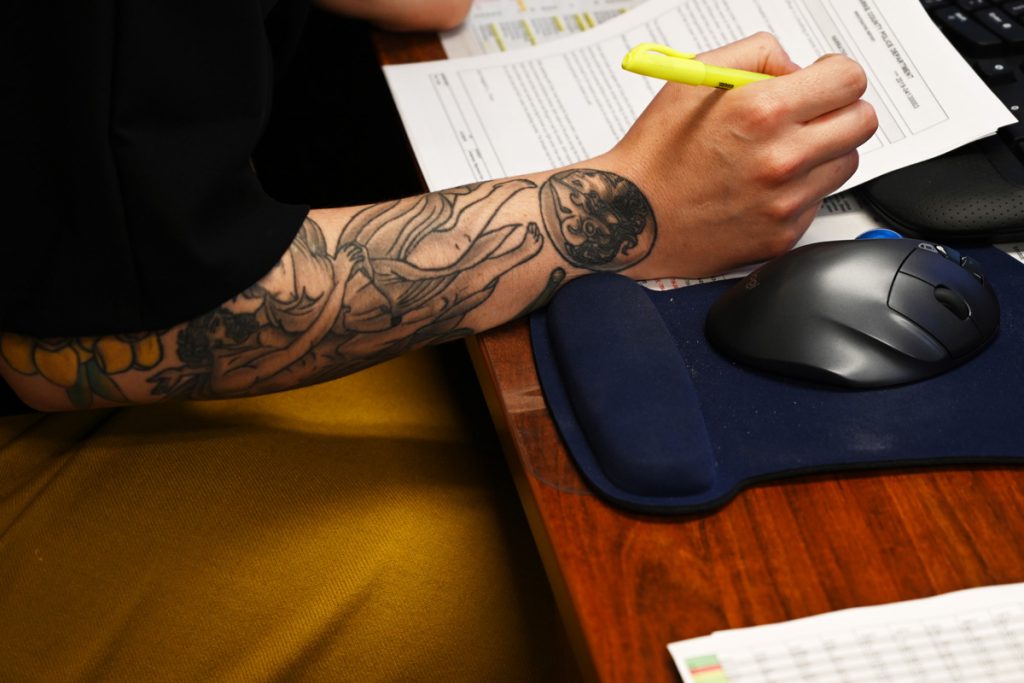

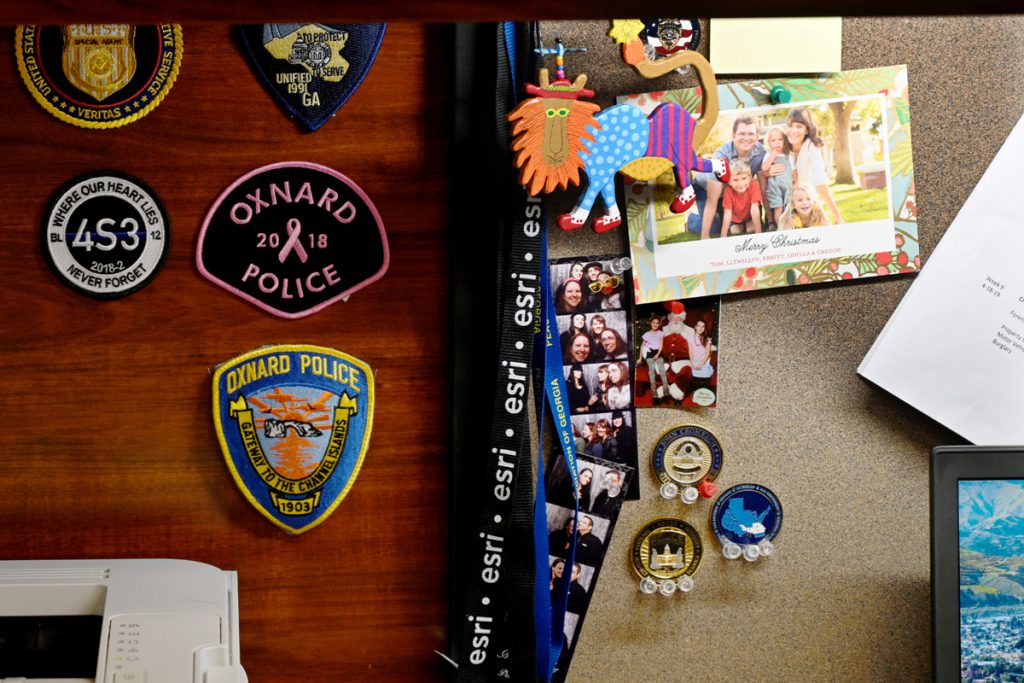

Bocanegra works in the Athens-Clarke County Police Department with David Griffith, 48, in the Crime Analysis Unit. Her new office still doesn’t have windows, but it does allow for more personalization.

At the 911 center, she sat at a different console every shift, so permanent personal decorations weren’t allowed. She now has pictures of her family hanging on the wall.

Bocanegra occasionally wouldn’t get a lunch break in dispatch, but now she has a mini-fridge.

She and Griffith compile crime reports from the previous two weeks and run them through a series of algorithms to create a crime map of Athens.

“There’s a lot of suspicion around predictive policing,” Griffith said. “We’ve tried really hard to eliminate bias.”

Griffith previously worked in the casino realm, tracking customer’s spending habits.

He and Bocanegra consider the geographic elements of a reported crime to see reoccurring trends. They are close to predicting 80 percent of crimes, though they aim to have that number as low as possible.

“We want our accuracy to be low,” Griffith said. “We hope [police officers] do go disrupt some crime.”

Although crime analysis isn’t as fast-paced as dispatch, the position allows Bocanegra to serve the public from the other side of law enforcement.

Instead of putting out fires, she predicts where they will spark to prevent the types of calls she used to answer.

“I very much enjoy it,” Bocanegra said.

I do think of it as continuing to keep officers safe but in a different way.”

Whitley Carpenter is a senior majoring in journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia.