The law-altering conversations about air pollution in Georgia did not originate in the Capitol building chambers that hosted them. They started between a group of friends in a living room in the small Madison County town of Colbert, Georgia.

Eight months of lobbying later, Governor Brian Kemp’s signed a law banning the controversial practice of industrially burning creosote-treated wood statewide. Georgia Renewable Power’s biomass plant consequently ended its well-known and criticized practice of burning wooden railroad ties covered in creosote to generate power, and Colbert residents said they are breathing easy again.

Why It’s Newsworthy: The lobbying efforts of a group of likeminded locals resulted in effective collaboration with the government and an impactful change in Georgia’s environmental policy.

An Aggravated Populace

The plant has faced local opposition since it initiated its operations in Colbert. As it began its scheduled burnings, complaints flowed into the inboxes of the city hall from angered neighbors alleging that the environmental effect of the burnings was also a risk to their health.

Tim Fowler, whose home is less than a mile from the plant, was among the first residents to raise the alarm about the creosote issue.

“You couldn’t breathe it was so bad,” he said. “We had to keep the windows and doors shut all the time. It was like we were prisoners in our own home.” Residue from the burnings noticeably began to accumulate on walkways and in yards, he said. “You could shine a flashlight at night and just see particles floating down…it would burn your eyes; make you cough.”

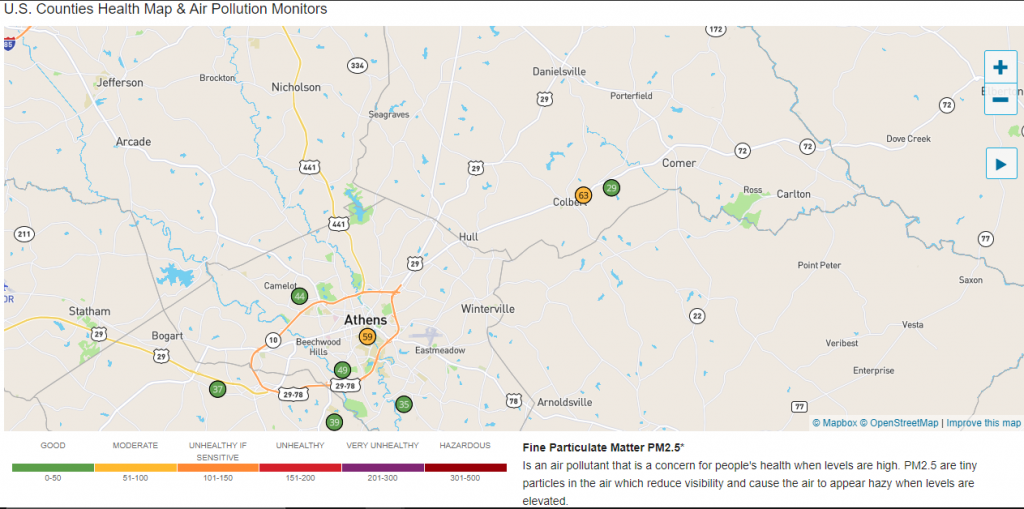

Weather Underground, an international weather and pollution monitor, classified this particulate matter as a PM2.5 micropollutant. These small particles are most commonly found in urban contexts, and according to the New York Department of Health, exposure to these pollutants leads to irritation of the respiratory system and allergy-like symptoms. If the exposure to these particles is prolonged, the risk of lung and heart disease can worsen drastically.

The worst part for Fowler, though, was far from the pollution.

“We enjoy country life, simple country life. Peace and quiet. Now that’s gone.”

A Pressured Operation

However, Georgia Renewable Power was not without its reasons for the power plant’s controversial burning, and Plant Manager David Groves remains optimistic that the facility will still benefit the county and its population.

Neither Groves nor the Madison County facility responded to attempts by phone and email to contact them.

However, Groves said to Mainstreet News that providing lucrative jobs and long careers to locals is a priority in addition the the $1.7 million annual tax revenue it brings in for Madison county.

As for the creosote controversy, Groves attributed the plant’s use of railroad ties to necessity rather than any ill intent. Upon its establishment, the Madison County plant entered into a 30-year contract with Georgia Power with a quota to produce 58 megawatts of power a year. Such a feat requires an impressive 40 tons of fuel per hour.

Groves also said to Mainstreet that to not burn the crossties would be to risk falling short of their contract’s quota.

From a Late Night to a Law

These conflicting interests have seen no shortage of visibility in the press, and “Letters to the Editor” columns of most local news outlets were filled with the worries of concerned citizens.

Some of these writing residents, nearly all of whom lived near the power plant, saw their neighbors’ concerns and contacted each other. Before long, a small group of neighboring strangers became fast friends over a common experience, met up in a living room and founded the Madison County Clean Power Coalition (MCCPC).

Ruth Ann Tesanovich, a founding member of the coalition, met Fowler along with others and was grateful to no longer be alone.

“People, neighbors, were brought together that would never have even met otherwise,” she said.

The coalition’s biggest limitation was obvious from the start. According to Tesanovich, their roadblocks stemmed from both the fact that they only had a local reach as citizens and were completely reliant on others to enact the change they advocated for.

The fledgling coalition held a publicized informational meeting about the potential harms of creosote burning in the cafeteria of Madison County High School on Dec. 5, 2019. Three hundred people attended, and among them was Georgia District 32 Rep. Alan Powell, R-Hartwell.

Twin bills for a statewide ban on industrial burning of creosote were drafted for both houses of the Georgia legislature the next week.

The environmentally conscious HB 857 drew the attention of the Georgia Chapter of the Sierra Club, a nonprofit conservationist lobbying organization. The Sierra Club contacted the MCCPC, and some of its members were cleared to testify for the Georgia Senate hearing of the bill.

Fowler testified to the Board of Natural Resources.

“It was a great experience to be able to go up there. I mean, that’s power there.”

Following the Senate bill’s failure to pass to the House, all eyes were on the second round of hearings before the Natural Resources and Environment Committee of the Georgia House.

During and after these hearings, the MCCPC made itself as vocal as possible to both the state and the county. Tesanovich started an “E-blast” campaign: everyone on their 300-member contact list was notified that the bill was in that committee and asked to contact its members.

In addition to local measures, the group also took up lobbying.

“There’s this time where they (legislators) come out of the chamber, and lobbyists really go and talk to ’em and they actually come out and meet people…” said Tesanovich, “I didn’t find that very effective; we went to their office.”

“We learned how to talk to the assistants that had direct lines to the representatives…We were all over the place.” said Tesanovich.

“We learned how to lobby; soon we were powerful.”

HB 857 was passed to the Senate on March 11. The pandemic shut down legislation the next day.

The combined weight of the extended shutdown of 2020 along with the racial issues that plagued it put the bill on hold. As the Georgia legislation tended to the pressing issues of race relations and crafting a post-pandemic budget, the MCCPC did not let their bill be forgotten.

Hard copy informational packets were sent to every state Senator’s district offices, which were also phoned by the now expansive roster of the MCCPC.

When the state Senate came back in session, HB 857 was passed unanimously and sent to the Governor’s desk. Effective on August 4, 2020, creosote was no longer to be burned for power in the state of Georgia.

“It was ecstatic…we were watching at home and were jumping up and down.”

‘It was not a political thing, it was about people’s health and quality of life.” Tesanovich said.

Since the law has passed, the Georgia Renewable Power biomass plant in Madison County has ceased the burning of creosote products. Relations between the facility and its hosting town remain contentious, but tensions have deescalated.

MCCPC’s effectiveness in their strategy gained the attention of the Blue Ridge Environmental Defense League, and they became a chapter in January 2021. The coalition has since branched into working with other states.

For Tesanovich and the MCCPC, empowering others to advocate for change is just as important as achieving it.

“They’re listening; they’re representing the people. They do listen to people and if you go there and testify you can make a difference. You can make a difference. People don’t know that.”

Editor’s Note: Until reaching college, the Newsource reporter was a resident of Colbert, Georgia.

Jared Gilstrap is a fourth-year majoring in journalism in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia.

Show Comments (0)